Chapter 23:

Non-art and self-creation in the art gallery

At art galleries young new visitors are of course met by the art, but also communication about the art in the form of labels, text, folders etc. This chapter focuses on three main areas: how this communication defines the visitor as a somewhat passive recipient of information; how the visitor performatively involves herself to construct her identity using the exhibition and the artist as part of the creation of identity; and how the visitor creates communication in the art gallery. This leads to a discussion of the conflict that arises between curators and visitors as well as a presentation of ten dilemmas to be addressed and resolved in the context of the art gallery.

How do art galleries meet ‘young new’ visitors? How do museums think about the communication surrounding the artworks? Who has the necessary knowledge and authority? Will the self-creation and self-experience that arises with young new visitors create new opportunities and alter the circumstances that currently clearly mark the division between art and the communication surrounding art? How do young new visitors encounter the museum? How can museums meet the challenge of receiving these visitors?

(1) … I am the recipient of information

In November 2007 when I was visiting the art museum ARoS in Aarhus, Denmark, I had my new cell phone along and at one point I saw something exceptionally outstanding and snapped a picture. The whir of my cell phone’s artificial shutter, which I had not yet learned to shut off, alerted a security guard who, after immediately appearing from around the corner dressed in black, asked: “You didn’t just take a picture, did you?” Caught red-handed with my cell phone, I told a white-lie, explaining that I had just received a text message. In reality, I had perhaps just taken an illegal photo [Ill. 23.1].

Ill. 23.1: Clandestine photo of Mariko Mori’s extensive photo manipulation, Kumano, at left. Note especially the woman standing in the silver ring listening. The ceiling loudspeaker is activated when visitors stand in the silver ring.

It was not the middle-aged woman that I found worthy of note, but rather what was happening where she stood. And where I stood. Standing in separate silver rings painted on the floor, we heard a soft, charming female voice speaking English with a typical Japanese accent. The voice narrated, ”In 1997 I went to the Kumano forest to reach the Nachi Waterfall. I walked for twelve hours and on my way I had a series of magical and supernatural experiences which I portrayed in the picture Kumano." [1]

It was exhilarating to see that this art gallery obviously no longer observed the traditional form of reverence demarcating artwork as a unique, sacrosanct work. In this instance the artist was present, telling about herself, her work process and the exceedingly complex, strange symbols that occur in her works.

Her narrative about Kumano helps us become familiar with the mirror as a cultural symbol and explains how her hairstyle is inspired by Buddhism and Chinese emperors. We learn about the Buddhist temple Yumedono, which she first encountered in a dream while walking in the woods, where she came upon a temple with a golden room.

Astonishingly, in this art gallery the artist is allowed to turn to us as visitors, providing us with numerous entrances to her work, enhancing our experience and contributing to making us as visitors privy to the universe of the artist. The atypical aspect of this approach is what makes it particularly surprising. This artist has a desire to communicate in a variety of different ways with her audience.

Consequently, the exhibition is remarkably challenging. There were three silver rings situated in front of each piece of artwork that provided access to different kinds of information. The idiolect in this exhibition comprises three rings, one in which Mariko Mori tells about her working process; one where she identifies and explains cultural symbols; and one where she explains the work itself in more detail.

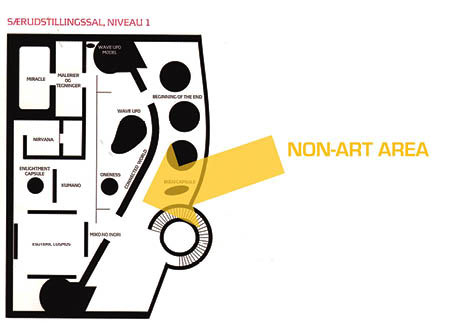

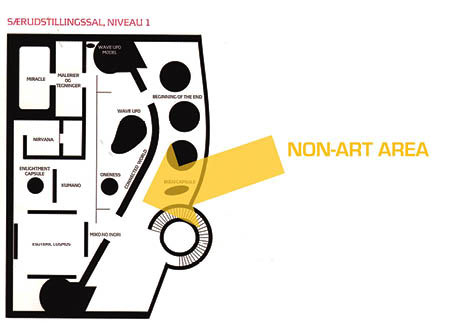

At this point I was unawares as to the inversion that awaited me. Outside the exhibition there was also something completely new, a NON-ART AREA [Ill. 23.2].

Ill. 23.2: Upon exiting Mariko Mori’s exhibition and beyond the “legitimate” art spaces is the NON-ART AREA. This area, in contrast to the fascinating works on display by Mori, is not shown on the map of the exhibition on the back of the museum’s folder.

The area, so conspicuously different, is not even represented on the map on the back of the museum folder showing the layout of Mariko Mori’s entire exhibition. Another peculiarity is that the room housing the non-art area also contains a number of the now familiar silver rings that are obviously meant to challenge your body and movements to teach you something. If you step on the silver rings then the pictures on a plasma screen change. There are banners that contain large amounts of text, but there is no artist describing herself or her work. In this area, it is another voice of knowledge that speaks and is particularly mediating.

This is confusing. In the art space it is obviously the artist Mariko Mori who emphatically and poetically extends and creates various entrances into her work. The three silver rings that allow visitors to activate the sound are a phenomenally simple and elegant concept of mediating.

This concept outside the art space is defined differently. Other voices are talking, but the silver rings no longer activate the sound. The rings activate another kind of language, where something different can happen. Annoying.

The physical and phenomenological experiences of space, work and that which is different than the work are one aspect, while a whole other aspect is the decisive communication issue of who is talking to whom?

In the art space Mariko Mori is talking through her works and through her poetic voice. We believe in her because we can relate to the images of her with a female voice with a Japanese accent. Consequently, we believe she is speaking from her own experiences and reflecting on them and on cultural symbols. She gives the impression of being a highly confident and reflective artist.

In the non-art area the voice is much more explanatory and speaks much more didactically about Mariko Mori. Obviously not her, the voice takes on the tone of an art institute, reflecting the diction used in the printed catalogue, “Mariko Mori’s spiritual turning point, however, was not concentrated exclusively on Buddhism. It is human consciousness as a whole that interests the artist rather than one religion more than another…” [2]

ARoS, on the one hand, employs a fine concept to guide the artist as a mediating player in the exhibition via the three silver rings that activate the sound. The non-art area on the other hand clearly indicates isolation and a dissociation to the mediating practises in the workspace. Although there is a difference between artwork and communication, must this necessarily be the case?

(2) … I use it to create my own identity

The security guard dressed in black at the art gallery wanted to prevent me from taking photographs. He was just doing his job to enforce the signs hanging everywhere saying no cameras, no video recorders, no cell phones etc. His task, however, is in opposition to the new practices developing explosively, especially among young people. New technologies and practices offer many different aesthetic and expressive options for communicating one’s tastes, style and identity (Michael 2000:35-6).

Photographing and being photographed move the attention to one’s own body, posture and clothes as well as to the relations one wants to expose to others: you pose and act in front of the camera. As Roland Barthes observes, “I have been photographed and I knew it. Now, once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of ‘posing’, I instantly make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image” (Barthes 2000:10).

This performative aspect of the visual moves the idea of photography as a picture of what has been to a kind of ‘new photography’ in which a picture becomes an indication of here I am. This moment is made possible by digital cameras and phones, which can be used to send pictures instantly via a multimedia messaging service (MMS) to friends the instant they are taken.

This here I am approach occurred in the museum and the exhibition, where the cultural milieu and the highly unique pictures or installations can be taken advantage of by young people to mark their style, their preferences and their inclusion and exclusion of others. This approach makes it possible to show others who you are with and who is sharing your experience and tastes.

The approach also involves the option of self-representation, posing and acting in front of the camera as an opportunity for the group to participate in the photographic process as a whole. More people can simultaneously choose to be photographed as well as where, and everyone can evaluate, criticise and choose the picture with shared content and what is the aesthetically ‘right’ picture.

This creation of identity is supported by the new visualisation practices and is obviously a process that involves the artist, the exhibition and the museum as elements in the users’ positioning of taste and thereby an involvement of culture as part of staging and producing here I am.

Many years ago the Canadian museologist Sheldon Annis wrote that one of the pragmatic aspects of visiting a museum was for visitors to be able to hang a scalp on their belts, i.e. now I’ve also seen the Mona Lisa, and Mariko Mori [3].

The performative aspect is propelled by the photography, the camera and now by an even more mobile apparatus and in the resulting practices that develop from the rather new way of looking at photographs and the world. Via documentation and rapid communication, art, exhibition and the museum can be involved and used.

The security guard said stop in a place where saying here I am, is not allowed, and especially not showing it! I told him a lie, but I would rather have stepped into one of the silver rings and asked him to take a picture of me.

The museum and the curators possibly saw this approach to creating identity as a means to influence the construction of an actual exhibition in order to provide a variety of different aesthetic and expressive opportunities for visitors to express their taste, style and identity. The opportunities would then be provided by not just the museum or the curators, but by young new visitors.

(3) … users create the content

The first ambiguity I tried to identify is the obviously difficult relation between the artworks themselves and the communication and mediation surrounding the artworks. Nonetheless one position is rather clear: there is someone who knows and wants to give their way of categorising and knowledge to people who are less knowledgeable.

The second ambiguity I tried to identify is that young new users might have other agendas than the art, e.g. self-representation, taste and style can be used to create identities and art can provide the background for a larger project. How do the museum and the curator handle this situation in light of the new practices of visualisation?

The third ambiguity involves posing a question: does the museum and the curator dare to let go of the communication and mediation and leave the content and form to young new visitors? Does this mean literally allowing users to create their own experiences? And does this mean something more than just individual experiences?

The OECD’s definition of user generated content contains three elements [4]:

1) Publication requirement (access for at least a selected group of people);

2) Creative effort (this implies that a certain amount of creative effort was put into creating the work or adapting existing works to construct a new one, i.e. users must add their own value to the work);

3) Creation outside of professional routines and practices (motivating factors include: connecting with peers, achieving a certain level of fame, notoriety, or prestige, and the desire to express one’s self).

Already in the 1980s the French theoretician of culture, Michel de Certeau, emphasised that in their daily lives people try to familiarise themselves with the huge amount of mass produced goods they use. People rebuild their own worlds and identities from available resources using a range of tactics by combining, adjusting and adding something else [5]- in addition to sampling, an aspect that has become more important today. The process of becoming familiar with what is mass produced is not creativity as defined by the romantic/modern notion of producing something new. This process is a creative tactic that, according to de Certeau, “... expects to have to work on things in order to make them its own, or to make them ‘habitable’”.

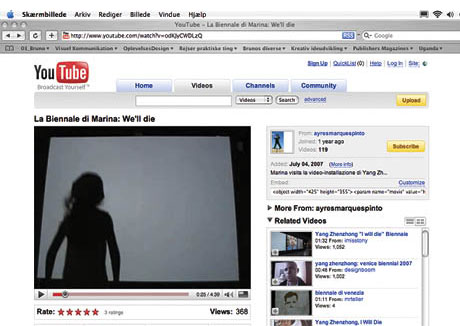

Ill. 23.3: YouTube, which contains this ‘new’ artwork, is an example of user-generated content with publication, creative effort and a creation outside professional practices (screen dump 6 June 2008). Ill. 23.3: YouTube, which contains this ‘new’ artwork, is an example of user-generated content with publication, creative effort and a creation outside professional practices (screen dump 6 June 2008).

Four minutes and thirty-nine seconds of user-generated content on YouTube [Ill. 23.3]: is this clip really an example of user-generated content that meets the criteria of publication, creative effort and being outside professional practices? The title, La Biennale de Marina: We’ll die, is visible as well as some additional text: Marina visita la video-installazione di Yang Zhenzhong. [5]

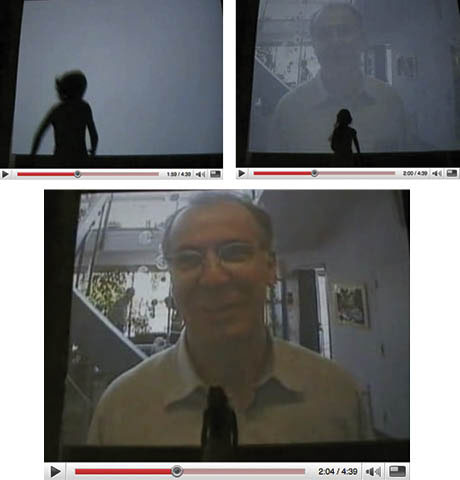

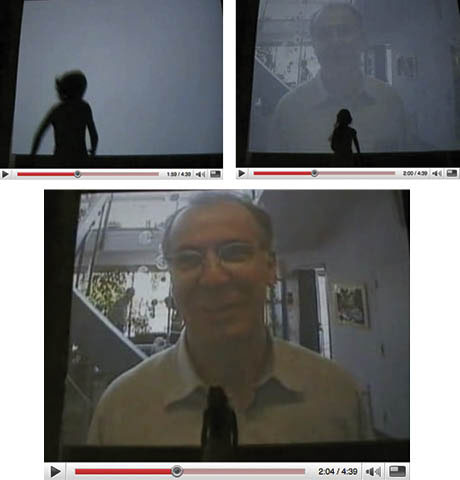

Published on YouTube and viewed 381 times [6], the video was produced outside professional practices, but is it more than just a reproduction of an artwork? What are the creative aspects? There are two central people in this intense art experience. One is the photographer and the other one is a little girl, who must be Marina, who is visiting the video installation [Ill. 23.4 & 5].

Ill. 4: Marina runs towards the huge video projections and stands very close to a man who says, “I’ll die”.

The video shows Marina running and jumping away from the photographer towards the gigantic portraits facing and addressing her and us. She stands extremely close to the video projection, a tiny human being beneath the giants. The soundtrack plays a myriad of voices that softly, thoughtfully, quietly, tensely, powerfully declare, “I’ll die”.

Marina runs along the many gigantic portraits, not so much to look at them as to move to the bottom of the row of projections. She does not look at them as she gets closer to them. Her actions, however, reflect precisely what the text says: Marina visiting Yang Zhenzhong’s video installation.

YouTube lists who has uploaded the video, namely ’ayresmarquespinto’, a 49-year-old Brazilian living in Italy named Ayres who works with therapeutic photography and is a cook. This information closely pertains to self creation by using the video and the little girl, consequently turning the video of the visit into a trophy or a recreation of what was produced in the process of making things liveable, what de Certeau calls ”...to make them its own, or to make them »habitable«”.

Ayres has the power of the camera and chooses where to stand and what to film. He sees himself as the creator of a new work. He sees Yang Zhenzhong’s video installation, but he turns it into his own work by seeing it through Marina and also by giving the work a completely new title, La Biennale de Marina: We’ll die, i.e. “We’ll die” and not “I’ll die”. He chooses from among the hundreds of people saying “I’ll die” in many different languages, and reduces the numerous hours of video in the original work to four minutes and thirty-nine seconds. He alters the tremendous physical space by reducing it in size to fit the tiny video screen on YouTube and he plays with the symbolism of dwarfs and giants by inserting a little girl into the room.

Hence Ayres’ video communicates about his experience, but the experience is dual edged. The first aspect of the experience is his work with “I’ll die” and the second aspect of the experience is the visit with his daughter Marina. There is however also a third and fourth experience: the staging of his daughter’s movements in front of the screens; and the future experience where, by visiting the publically available site YouTube, Ayres, his daughter and we can watch and re-watch the video months or years from now when the exhibit has been taken down. Ayres and his daughter can also use the video to cue their memories of their trip to La Biennale.

Ayres generates content; he is creative; he makes the strange familiar. But he does so outside the exhibition space, where his experiences took place. Is it possible to imagine the museum and the curators actively working to contain and develop this kind of user-generated content?

The Rumanian-American creativity researcher, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, thinks that an important factor for creativity of any kind is to have a medium, or as he calls it, a domain.

Returning to the ARoS example with the three silver rings, picture putting three rings into another exhibition in front of each piece of artwork. Viewing the silver rings at this point as a domain, they can be used as a sensor-activated format by stepping into them under a loudspeaker to produce two-minute sound sequences. It is now possible for users who are interested in doing so to create some sort of sound or mood for the artwork by finding a sound or music, designing a sound, sampling a sound, recording their voice, interviewing, reading a text aloud etc. The newly created sound could then become part of the exhibition, either immediately, after 15 minutes or after a user-defined period. Once installed it could remain part of the exhibition for a few hours, days, weeks etc. based on a given selection and replacement strategy. The options are endless. For example rules determining who can use each ring could be established. The first ring, for instance, could be for children twelve and under; the second one for women over the age of 50; and the last one some other age group.

When designing and promoting user-generated content three basic guidelines must be followed:

- The first and most decisive guideline: Visitors must create the content of the communication and mediation. With no exception and no censorship!

- The second guideline is to establish what Csikszentmihalyi calls the domain (of the media or format), which then has to be explicitly defined in clear and transparent rules that provide opposition by simultaneously forcing and supporting creativity.

- The third guideline: Provide personal and material support for finding and technically producing a sound bit.

The question must be asked, however, as to whether every visitor feels compelled to create user-generated content. The American theoretician of new media, Lev Manovich, shows that not every user becomes a producer. His findings indicate that only 0.5-1.5% of users on the most popular sites, e.g. Flickr, YouTube, Wikipedia, upload their own content (Manovich 2008:2), but that 65,000 videos are uploaded daily on YouTube [7]. Extrapolating from these figures and applying them to Denmark means that a small museum like the Museum of Contemporary Art in Roskilde would generate about 120 users interested in participating in self creation and that a large art gallery like Louisiana would generate about 4,000 users each year.

I want to stress that the highly active involvement of users as co-producers of the content of an exhibition and the communication and mediation of the art influences the art and strips the professional institution of some of its customarily central practices. Might becoming emancipated from these customary practices not lead to new and well-known forms of communication, mediation and self creation being liberated to create new spaces of learning?

Notes:

[1]

This text is derived from Oneness: Mariko Mori, p. 22.

[2] From Oneness: Mariko Mori, p. 22.

[3] Annis, Sheldon (1994): ”The museum as a staging ground for symbolic action” in Kavanagh, Gynor (ed.): Museum Provision and Professionalism, Routledge.

[4] OECD: Participative web: User-created content 2007, p. 8. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/57/14/38393115.pdf

[5] The Practice of Everyday life.

[6] On 6 June 2008 at 12:26 PM, the video had been viewed 381 times. On 28 March 2012 the video had been viewed 726 times.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odKJyCWDLzQ

[7] Manovich 2008:3.

|