Introduction to the theme:

Questions - Experience and learning processes

“In the beginning was – not the word – but the experience”, writes Professor Lisa Gjedde in the first line of Researching Experiences: Exploring Processual and Experimental Methods in Cultural Analysis, published by her and I in 2008. Our main goal was to find methods to overcome the gap between the experience and recounting the experience by asking:

… what experience are the users actually talking about? Is it the experience they had in the actual moment or is it the one they constructed minutes, hours, days or years afterwards? And, what is the content of the experience? We focus on capturing not just the part of the experience that can easily be verbalized, but also the pre-reflexive experience, which has not yet entered the realm of conscious expression and may never reach it (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:1).

The questions posed in the above quote point to the complex field of experience and learning that e.g. John Falk and Lynn D. Dierking write about on the Experience Model. But in this introduction I will go further than Falk and Dierking and present a theoretical framework that goes deeper into the experience processes and also into the unconscious and creative processes of the experience.

Pragmatist John Dewey describes what we broadly call experiences as mainly being daily practices that we do not have to make an effort to reach or that arise because of extraneous interruptions or inner lethargy. He explains that, “… we have an experience when the material experienced runs in course to fulfillment” (1934/1980:35). In an experience, flow is from something to something and leads to an ending as some kind of narrative. In relation to exhibitions and museums and experience, Dewey states that there is always a material point of departure for the experience:

A work of fine art, a stature, building, drama, poem, novel, when done, is much a part of the objective world as is a locomotive or a dynamo. And, as much as the latter, its existence is casually conditioned by the coordination of materials and energies of the external world (1934/1980:146).

When Dewey finds that an experience must have a materiality in the external world and that it must have some kind of narrative with an ending – he also underlines the important action of the user, “For to perceive, a beholder must create his own experience. And his creation must include relations comparable to those which the original producer underwent” (Dewey 1934/1980:54). Dewey indicates that the user has an obligation to be open and give as much attention as possible to follow the producer of the exhibition and not to be disobedient or get other peculiar ideas and thoughts. In other words, to not be too creative.

How – handling an experience

Based on our research on the construction of the experiences of visitors at exhibitions and museums or with webart and interactive media, we realised that we needed an increasingly detailed framework for experiences and based on our fieldwork we constructed a theoretical framework inspired by British psychologist Frederick Bartlett and his work with narrative structures and memory (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:99-114).

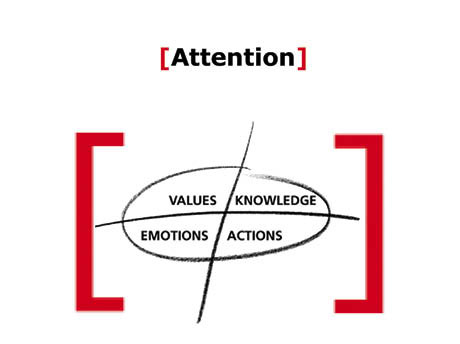

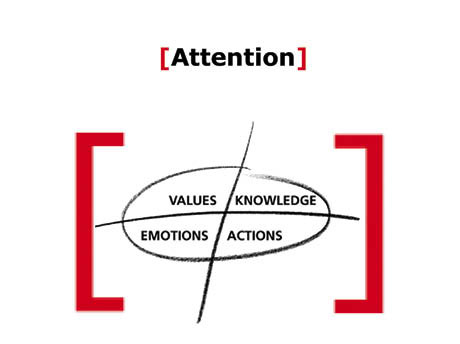

Ill. 7.1: The Attention Model – (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008).

The Attention Model consists of the four fields of experience: values, emotions, knowledge and actions [Ill 7.1]. Our book describes the model as follows:

Attention is directed by the person-in-situation in daily life. John Dewey (1934) states that attention is that which directs the experience: Without attention, no experience. By making this claim he sorts out most of what we call experiences because we need to make a mental contribution to have an experience. Events are not in themselves experiences: The entertainment at an amusement park is not in itself an experience. You can be physically present at a noisy event and only observe the happenings and this is not what Dewey would call an experience. You need to give attention to the situation and this attention-giving also holds the potential to create meaning about what is in front of you.

The field of values can be expanded by relating it to the work of psychologist Milton Rokeach, who has worked within this field since the 1960s. He states that, “… a value, unlike an attitude, is a standard or yardstick to guide actions, attitudes, comparison, evaluations, and justifications of self and others” (Rokeach 1968:160). He believes that there are thousands of attitudes in a person’s belief system and that they are cognitively connected to around two dozen instrumental values and that they are functional and cognitively connected to fewer terminal values.

Several years later he named the following eighteen instrumental values: Ambition, helpfulness, capability, politeness, honesty, imagination, obedience, intellect, being loving, logic, courageousness, independence, broad-mindedness, cleanliness, responsibility, forgiveness, cheerfulness and self-control. The terminal values are: A comfortable life, an exciting life, a sense of accomplishment, a world at peace, equality, family security, freedom, happiness, inner harmony, mature love, national security, pleasure, salvation, self-respect, social recognition, true friendship and wisdom (Rokeach 1973).

If you are interested in, e.g. gender differences then the constructed values of men and women are important values. But what about religious values? And cultural values?

The field of emotions can be put into perspective by drawing on the works of neurologist and philosopher Antonio Damasio, who has developed a theory of emotions mainly by distinguishing between primary, secondary and background emotions. Primary emotions are innate emotions: Happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust; secondary emotions are social emotions such as embarrassment, jealousy, guilt, and pride. Finally, there are background emotions such as well-being, malaise, calmness and tension (Damasio 2000:50ff.). Background emotions do not use the differentiated repertoire of explicit facial expressions that easily define primary and social emotions. The features of being tense or edgy, discouraged or enthusiastic, down or cheerful are detected by subtle details of body posture, speed and the contour of movements, minimal changes in the amount and speed of eye movements, and in the degree of contraction of facial muscles. What is important for us is the fact that all these different internal states are ordered along a continuum. Descartes made the error of failing to separate emotion and reason, whereas now it has been experimentally proven that reason is influenced by emotion (Damasio 2000: 57).

Mood, aesthetics and narrative are part of the emotional field. Users begin their experience before getting to the ‘real-thing’, e.g. the exhibition at the museum. In their excellent book on the museum experience, Falk and Dierking note that it does not start in the exhibition but in the foyer and even earlier in front of the museum (1992). An emotional attitude toward the whole museum is created by the physical setting, which is created by the architecture and design that includes elements such as space, colour, texture, material, line, typography, structure, layout, composition – and, at times, dramaturgy and the placement of contrasting or commenting elements.

The narrative can be understood in a dual way. Narrative is often presented in the work, video, exhibition, or magazine, which tell a story by using the above mentioned elements, but also by using characters, plot, conflicts and solution in the creation. In addition to these aspects, users combine the complex elements they encounter in the work to create meaning out of chaos. In this process, the narrative is used to construct meaning, after which users make their experience available to the researcher by telling the stories they constructed in order to make meaning.

The field of knowledge refers to the cognitive content of the communication. The person-in-situation gains new information about something in the process of perception and also relates this to what she already knows since one cannot gain new knowledge without relating it to old knowledge. Geoff Loftus and John Palmer, as mentioned earlier, describe this as a process of combining information from different sources, stating, “Two kinds of information go into one’s memory for some complex occurrence. The first is information gleaned during the perception of the original event; the second is external information supplied after the fact. Over time, information from these two sources may be integrated in such a way that we are unable to tell from which sources some specific details are recalled. All we have is one ‘memory’” (Loftus & Palmer 1974:585-589).

While there is reflection going on during the situation, in a dialogue with the user about what they experience, and also in the choices they make, another level of reflection can be triggered by making informants review the experience and comment on it after it has been completed. This means that the researcher can make use of designing what we call a ‘reflection gap’ in the process of creating a framework for reflection and obtain some distance to the full experience.

Recordings of the person-in-situation on video or audio allows one to listen to quotations from the mediated experiences, and fragments of words and sentences that have made such an impression that they have been integrated into the spontaneous talk. In the interview conducted after experiencing the work, these video and audio recordings are presented to the person-in-situation as important retrieval cues that can help the informant remember and produce knowledge. This knowledge contains the new knowledge, the old knowledge and the external knowledge gained after the original event or maybe in the process of reflection interview.

The field of actions presents the person-in-situation engaging with the body in a reflective and pre-reflective mode. It also relates to the potential of reflection-in-action (Schön 1983), where your actions are expressive of an underlying knowledge of “thinking with your feet”, of artful doing based on your immediate experience of the situation. The field of actions is often explored by asking informants to make choices, either by choosing and ranking artefacts or by navigating physical or virtual spaces.

In all our social relations we use our body to create the distances of intimacy and distance, trust and power. Edward Hall’s (1966) prosemic theory shows that this body language is culturally created but also in its daily use rather unconscious but effective.

If, for instance, you stand alone in an art gallery in a big room and another person enters the room, you are aware that she is there. If you move towards her and place yourself a half a meter from her, then she could apprehensively choose to move away because you may have violated this person’s personal zone by exceeding her safe distance.

The semiotician Edward T. Hall demonstrates that we have unconscious barriers that determine how close we allow other people to come to us and our bodies, explaining that, “... each one of us has a form of learned situational personalities. The simplest form of the situational personality is that associated with responses to intimate, personal, social, and public transactions” (Hall 1996:115).

Hall finds that ’close personal distance’ is the distance where, “one can hold or grasp another person” and defines it as “the distance of the erotic, the comforting and protection”. If someone we are not intimate with comes too close, we experience it as aggression. Hall defines ’far personal distance’ as the distance that, “extends from a point that is just outside easy touching distance by one person to a point where two people can touch fingers if they both extend their arms”, a distance where “subjects of personal interests and involvements are discussed” (120). The boundary between the far phase of personal distance and the close phase of social distance marks the ‘limit of dominants’.

Another type of distance that Hall defines is ’close social distance’, which begins just outside this range and is the distance at which impersonal business interaction occurs. People who work together tend to use close social distance. The distance to which people move when somebody says, “Stand back so I can look at you” is defined as ’far social distance’. Business and social interaction conducted at this distance has a more formal and impersonal character than in the close phase. Finally, ’public distance’ is outside the circle of involvement and is connected to representative occasions” (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:158).

The four fields are analytical tools to guide the researcher on how to observe and talk about the action, the emotions, the values and the knowledge created during an experience.

Why are experiences so important?

It may easily be accepted that attention is necessary for the visitor to create an experience and learning. But why do visitors find it at all necessary to invest energy and especially time to look at an exhibition? There must be something that determines this other than just the topic of the exhibition or the design of the exhibition room. The HOW fields are theorised in the Attention Model and the WHY perspectives are theorised as the four gazes in The Reading Strategies:

A theory of reading strategies and the values that are important to the reader needs to include the aesthetic and referential in relation to topic, expression and content; it needs to include the personally relevant and previous knowledge; it needs to capture that the actual readers’ values are not constant but are fluctuating all the time and through the reading act there is a shift between different reading strategies. The theoretical frame gathers the aesthetic, the referential, knowledge-related and emotional elements in four gazes: The Locked Gaze; The Opening Gaze; The Pragmatic Gaze and The Reflecting Gaze. (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:19 & 69-73).

Ill. 7.2: The four gazes: Four Gazes: Reading Strategies (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008). Ill. 7.2: The four gazes: Four Gazes: Reading Strategies (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008).

The four gazes: Reading strategies

The theory of the four gazes was initially developed in relation to photography and then later applied to museum exhibitions. We have been asked many questions concerning the scope of the theory, the difference between gaze and look, the objects looked at and what consequences the theory has for the development of apprising the thinking of the person-in-situation. We can start with a rather different concept of the gaze. In their excellent book on photography, Reading National Geographic, Catherine Lutz and Jane Collins state that photographs, “… are objects at which we look” and they continue, “The photograph has its quality because it is usually intended as a thing of either beauty or documentary interest and surveillance” (1993:188).

Lutz and Collins have a critical view of the ‘gazes’, looking only at the formal features of the photograph alone, stating, “… we will argue that the lines of gaze perceptible in the photograph suggest the multiple forces at work in creating photographic meaning, one of the most important of which is reader’s informed interpretive work".

In their research on National Geographic photos, they identify the following seven gazes: The Photographer’s Gaze, which represents the camera’s eye and all the formal characteristics like point-of-view, sharpness, angle, framing etc.; The Magazine’s Gaze, including the editorial choices involved at the start of an assignment, editing the pictures and stories etc.; The Magazine Readers’ Gazes is seen mostly as the actual readers in the personal, educational and social pre-destination and subjectivity; The Non-western Subject’s Gaze is how and where the subject in the photograph is looking: at the photographer, another subject in the frame, into the distance etc.; The Direct Western Gaze actually shows white Western travellers in a local setting in relation to the natives; The Reflected Gaze of the Other, where the native sees themselves as others see them, e.g. as shown in a photograph or in a mirror; and, finally, The Academic Spectator, an extension of the reader’s gaze that represents the authors’ racial, national and educational backgrounds.

They define the photograph as an intersection of gazes, but even they are critical, looking only into the content and formal qualities of the photographs. Even if they stress the importance of the reader’s interpretive work, they tend to analyse the photographs themselves as signs or tokens of the multitude of gazes.

When looking into readers’ responses, they quote the findings of Tamar Liebes and Elinu Katz (1990) from their reception studies of the television series Dallas in such differing countries as Israel, Japan and the United States. They categorise their responses as lucid (playful), aesthetic (focused on the show’s artfulness or genre faithfulness), moral (passing judgment on characters’ behaviour), and ideological (concerned with latent, manipulative messages inserted by the show’s producers).

Looking at how fifty-five Americans react to the twenty photographs taken out of context to make them clarify the attitude toward the native in the non-Western photographs, Lutz and Collins conclude that in their readers’ preferences and identification, “… play and aesthetics are paramount” (1993:269).

This way of thinking about the Gazes involves more than just looking. It is more than mere perception, where the eye just looks at the objects in front of it, namely the photograph. I agree with the above construction of gazes, but believe something is missing.

First of all, the idea of locating the meaning in the picture itself is rather problematic, but can be divided into three elements of transaction, the first of which is what I call the appearance of mediated reality. The second element of transaction is the attention and involvement of the reader, the viewer or the user to give mental energy and respond to the appearance in the form of approval, joy, fear, boredom etc. The third element of transaction between the person and the object is the goal one has to be entertained, to become a valuable citizen or to create a good life for oneself (Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton 1981:175).

The three transactional elements are appearance, the mental involvement and the goal of the person – and this is seen by a third person looking at a person-in-situation. These transformational elements are the foundation for my creation of the four gazes as informed by the research process of my Mirage_Project in analysing the complex material of ranking and talking about news photographs (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:13-34). The decisive point became not to look at the photographs in themselves as bearers of gazes or into the psychological aspect of the individual, but to look at the gazes as reflectional constructions where the intentions of the pictures and their senders and the intention of the reader or user melts together into reading strategies. These gazes cannot be consciously explained by the user in themselves, but they are constructed in the reader’s use of her body and in the user’s dialogue or in the telling taking place during the interview and that can be analysed afterwards.

This means that what becomes the material to be look at will be some kind of mediation in the research practice that can be prepared in advance: The situation – the recording – the analysis – are the headlines for the projects, where one can go into the process of finding how the four gazes – the reading strategies - are active and what role they perform in the creation of meaning.

When analysing interview material where informants have been looking at mediated material, the four gazes can of course be used. Clarifying the intention to do so beforehand makes the process clearer and the findings richer. Now it is time to make some reflections and decisions about the situational, the recordings and the analytical process. Here, we want to further develop the formulation of the four gazes in the process of finding topics or themes to focus on.

The reflecting gaze focuses on the picture used as a mirror – not of reality but of the user in terms of inclusion or exclusion:

Identification with the situation, the person in the picture, i.e. ‘This is exactly like me, like I feel, like I want to be’.

I – the other is more value driven to find and distance itself from the unknown, the strange and the weird in words of disgust and distrust, but also the opposite of fascination, longing and closeness.

The pragmatic gaze focuses on what the reader can learn from the media and what can be of practical use:

Relevance is highly important in determining the pragmatic use of the picture or the information, i.e. is it useful in daily life to solve practical problems? Useful in the everyday world as practical knowledge? Or useful knowledge in society to act as a responsible citizen?

Explicit is an urge to have the information made unambiguous and clearly contextualised, to be told what to do with the information.

The locked gaze focuses on the photograph as a categorical picture that is a stereotype and primarily confirms the schemes the reader already has:

Categorical is the overall way of understanding by finding similaities to what the user already knows and avoiding and rejecting any disturbances in the appearances.

Referential is meaning in the informational content of the photograph or other media products leading to high trust, i.e. seeing is believing.

The opening gaze focuses on the photograph that in itself has inherent qualities and demands an open-minded attitude from the reader:

Poetic adds important aesthetic aspects to the appearance to expand the experience of the content.

Emotional can be surprising and sometimes provocative but is always part of the response to the actual experience.

In an actual project, these reading strategies have to be broken down into detailed, more concrete questions that need to be on the researcher’s agenda as themes in the questions to be asked about the situation and in the analytical situation.

The intersection of reading strategies is important to stress. As research tools they can be used to look into the actual dialogue and gestures and then in the interview to find the ever changing use of different reading strategies.

I have now presented the theory of The Four Gazes: Reading Strategies without relating it particularly in relation to exhibitions and museums because this will be unfold in one of the following chapters in this section. Here I will stress that the theory of the four gazes can be used to analyse and discuss questions about why people come to exhibitions and why they sometimes feel themselves excluded and other times they feel animated. They come with a motivation, a goal and knowledge and these preconditions determine their experience and learning as something placed in their daily lives.

- and now to learning

I am interested in what or how visitors learn during an exhibition and I am not talking about learning from a specific theoretical point of view, but from the way the person-in-situation experiences the exhibition and the learning related to the creation of meaning. In their book about the experience of learning, Ference Marton and Shirley Booth summarise the six concepts of learning as follows (1997: 38):

Learning as primarily reproducing

A … increasing one’s knowledge

B … memorising and reproducing

C … applying

Learning as primarily seeking meaning

D … understanding

E … seeing something in a different way

F … changing as a person

Conceptualising how learning is experienced does not bring us closer to the actual situation where the experience takes place. We can, however, draw on the research of Gaea Leinhardt and Karen Knutson concerning the use of conversation analysis in the museum setting. They propose that informal learning processes can be seen in the conversation that occurs between two people, e.g. in a museum. They examine the structure of the conversation and identify five structural codes: list, personal synthesis, analysis, synthesis and explanation (2004:84). And they define the learning that is constituted within these structures as, “… what a group talks about, it thinks about… what is remembered is learned” (2004:159).

The overall tendency here is not to prove whether mediated material is useful for communicating a rather clear and intentional message, but that the whole way of thinking within a social-cultural theory is that what is experienced, and especially talked about, is also learned.

Chapter 8 - Museums are good to think with focuses on three concepts various scholars have used to approach the relationship between the exhibition and the visitor. British sociologists Gordon Fyfe and Max Ross do not explore the museum and the visitor but focus on the informant’s leisure and class consciousness - and then involve the museum’s role in the informant’s creation of social identity. John H. Falk and Lynn D. Dierking are preoccupied with whether we can actually learn something concrete at a museum and especially how memories of exhibitions are recalled over time.

My approach is to examine how an exhibition is experienced while it takes place and then to add the informant’s reflection-in-action, i.e. how selected visitors at an exhibition talk with and about what they see and experience. This leads to a discussion of experience, learning and social identity in relation to the visitor and their experience of being included or excluded by the museum.

The three subsequent chapters take a detailed look at actual visitor experiences and learning in a cultural history exhibition, an art exhibition and a multimedia artwork about Nordic mythology. In order to study the person-in-situation and their experiences, they were videotaped as they moved through the exhibitions and artworks. The methodology behind this analysis of person-in-situation is fully presented in Researching Experiences: Exploring Processual and Experimental Methods in Cultural Analysis.

Chapter 9 - Person-in-situation (1) – Experience and strategy analyses a young woman’s visit to an exhibition in Copenhagen on democracy in the city. The analysis focuses on how her goals and previous knowledge guide her selections and dialogue with her friend as well as her exploration of the exhibition. The frame of the analysis is The Four Gazes reading strategies and how they make it possible to get a deeper look into what is experienced and learned. The young woman focuses on creating herself in relation to time and personal experiences, but she also overestimates the role of design as a topic in a somewhat awkward but well-argued way.

Chapter 10 - Person-in-situation (2) – Experience and questioning examines the visit of two men, one old and one young, at an art exhibition on a famous Danish artist named Ole Sporring. Actively searching after a framework to embed the experience of the artwork in, the two men turn the whole visit into a learning environment. Instead of relying solely on art history, they introduce knowledge and experience from their daily lives. In addition they unconsciously try to transform the artworks and the ambience of the exhibition into a shared narrative with a beginning, middle and end. Csikszentmihalyi and Robinson’s theories (1990), as related to theAttention Model, frame this chapter.

Chapter 11 - Person-in-situation (3) – Experience and interaction looks at the complexity of interactive multimedia in the context of the exhibition. The framework of possibilities is met by the users with confusion but also guided by the social interaction between pairs of users. Their dialogue and what they wonder about are influenced by their bodily actions and their knowledge of each other. Surprisingly the informants were highly aware of the social environment and also influenced by being in public, i.e. by the fact that others could see their choices and hear what they talked about. The learning process thus went beyond the topic of the interactive film on Nordic mythology. In this complex setting the narratives were the approach that guided the users and the researchers.

Chapter 12 - What is the question? Creating a learning environment in the exhibition attempts to uncover if it is possible to create curiosity and reflection at a science centre by stimulating and facilitating dialogue. The background for this approach was the vast amount of studies showing that free-choice and unstructured school trips result in little (if any) student reflection. The simple method used involved presenting a clear question to the students that put them in the role of the researcher or explorer whose goal was to examine many daily happenings framed by science. We found that in addition to facilitating curiosity and reflection, the approach helped the students have a good recollection of the visit one year later and that they had applied the insights gained from their visit. Thus, a dialogical approach constitutes a fruitful tool at science centres and most likely also in the context of other museums such as art museums.

Chapter 13 - Speaking places, places speaking – A transvisual analysis of a site examines learning from the point of view of a creative production of an exhibition. The chosen site is Paris, or more specifically, sites where there are McDonalds’ locations in Paris. This chapter introduces the analysis of a site not only by using words but also by transforming the complexity of the physical surroundings, houses, streets, places, cars and people into digital photographs. This new transvisual analysis reveals surprising aspects of Parisianness and of values and knowledge of the producer as the final series of pictures is selected, mounted and presented in the context of an exhibition. The learning that takes place involves not only the content of the site but also what the practitioner learns as seen through the framework of Donald Schön’s reflection-in-action.

|

Ill. 7.2: The four gazes: Four Gazes: Reading Strategies (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008).

Ill. 7.2: The four gazes: Four Gazes: Reading Strategies (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008).