Introduction to the theme:

Openings

– Category, objects and communication

Exhibitions and museums are primarily a means of dissemination and communication, whose attention is focused on visitors/users. This means that the most important actors in the communicative process are the visitors and how they dialogically use and interact with the exhibition as a whole. Theme 4 of this book centres on the sender or the producer and designer of new exhibits and on the considerations that must be taken to achieve visitor-oriented communication.

The museum inspectors and curators I encountered were remarkably interested in marketing and getting more and more people to visit their museums and the subsequent income, but they were surprisingly less interested in how they approached communication on site. I quickly discovered that they had a relatively narrow view of communication, primarily defining it as what was in text panels. It is however much more than that and includes videos, sounds, smells, movement, interaction – and talk, i.e. also talk between visitors and not just from the curators or educators to the visitor/user. When seriously broaching the subject, we found that we did not totally disagree and yet the explicitly formulated argumentation had an underlying tone of unease and unspoken objections. As it turns out, the objects and categories the objects were placed in were sacred and untouchable.

The chapters in theme four present questions and discussions based on the communication situation that exists in the network of museum people and its various discussion groups and outsiders like me. One of the key issues turned out to be authenticity.

One of my main research interests is photography and especially news photography. In one of my projects the goal was to see with the eyes of the readers and users of newspapers. The aim of this reception project was to show how ordinary people, and not journalists or editors, related critically to examples of manipulated photographs on the front page of a newspaper and to how newspapers twisted the reality and event behind the photographs. Sixteen people were told what had been manipulated and were thus aware of the transformation of a real event into a partially fictional story that could also possibly prove to be threatening for the people involved in the event.

The informants clearly related to the various forms of authenticity in a manner that was startlingly different from the attitude of the professionals. The extended individual interviews with informants show three different attitudes toward so-called authenticity or the relationship between the photograph on the front page and the real world. The attitudes among the informants toward authenticity can be divided into three positions. The first attitude toward authenticity was the naturalistic position, which focuses on the production circumstances; the second was the pragmatic position, which centres on how the people in the picture were represented; and the third was the constructivist position, which focuses on the image created by the media (Ingemann 1998:23-32).

What is an authentic press photo? Can hyper photos that look like real photos but that are actually composed of parts of other photos be considered authentic when placed in the context of a headline and a text about e.g. racism and a burning cross on the front page of a newspaper?

The informants take different positions. Some of the informants feel quite reluctant about the hyper photos. For them it is crucial that the film negative remains untouched, even though a picture’s quality is tied to the production circumstances. They hold a naturalistic position, i.e. what you see in the picture is what was in front of the photographer’s camera. Preferably, the images must function as data, a feature that allows the photo to retain its truth value and authenticity. This position is often touted by the press’s own people.

The newspaper makes use of the picture in a context. This focus on the use of the image leads to another kind of authenticity. On the one hand the image must give a fair representation of the people in the picture and in such a manner recognisable to those being presented. On the other hand, the picture should also match the perceptions readers have of racism. The image of a large burning cross is generally perceived by the participant and by the reader as manipulative. For informants who take a pragmatic position, the physical manipulation is less important than the psychological manipulation.

Despite the violent and powerful emotional content of a burning cross, some of the informants discuss and accept that as long as the image is informative it does not actually matter whether it has been manipulated or not. Informative images must live up to the reader’s wishes that the people in the pictures are presented in a way that they themselves can accept and that readers do not feel they have been emotionally manipulated by the image.

Informants negotiate with themselves about the meaning. They mostly relate their media-defined images of racism with race riots. Consequently they are taking the constructivist position, where the lengthy discourse in the media positions this particular article as an artefact – i.e. as an artificial product. The readers must decide if it should enter into their consciousness as a fact. The informants however do not accept the article and image as a fact, thus relegating it to being a picture artefact. Stripped of meaning, it becomes an empty object and not information.

Although almost all of the informants are dismissive of the physical processing in the example provided, their reasons for doing so differ considerably. One-third of them are resistant because they do not want photographs to be manipulated. The rest are dismissive because they do not want to be manipulated. The ethical debate moves from dealing with the production circumstances to centring on the use of the image. Thus it is no longer a discussion about the physical manipulation of the image but about the relationship between the reader and the image.

On the surface this research project on news photography does not seem especially relevant to exhibitions and museums, but it is to museum and exhibition objects – be they real or copies. The context and the authenticity in the relationship between visitors and objects in a certain context reveals more about what issues are problematic and makes it easier to deal with and discuss them. “It is not my problem but someone else’s”, as one curator exclaimed.

This concept of coming from an unexpected position opens up for challenges that are often closed and difficult. It is always easier from the outside to see what is happening and to get a brilliant idea or to dig into other people’s problems and the relations between objects, contexts, situations and users. This is also the case when it comes to the other core issue, namely the taxonomies, categories and dialogical communication.

Communication and dialogue

There are two classical textbook examples among teachers specialising in communications that involve a description of a giraffe (Jensen 1987:101).

Example 1:

Since ancient times the familiar giraffe (Giraffa) with its peculiar long legs and neck has been widespread across Africa’s open Savannahs. Its body is approx. 21/2 m long and at its crown it stands 5-6 m tall. The tail is long and ends in a tuft of hair. In the space between the forehead and ears both sexes have a pair of hairy horns. Some breeds also have another pair of horns on their necks. Stretching the length of the back of their necks is a short, upright mane. Their coat is made up of numerous dark brown patches separated by lighter hair (...) Giraffes feed on acacia sprigs and other trees, snatching food with their long tongues and using the lower incisors and canines to masticate.

Example 2:

Giraffes are the tallest animals on earth. They can grow up to six meters tall. They live in open country, but strangely enough it is still difficult to catch sight of these big animals from a distance. This is of course due to their colour, which blends in well with their surroundings the majority of the year. Their coat has a large quantity of dark spots separated by a lighter brown. Giraffes run fast, but frequently lions still manage to surprise them. It almost always happens at waterholes when the giraffe stands with its legs astride and drinks. Lions sneak up, jump on the giraffe’s back and kill it.

The first description is characterized by a taxonomy closely related to a professional classification. The emphasis is on a precise (anatomical) description of the giraffe in a specific order from its appearance to its diet. Textbooks contain similar taxonomical descriptions of other animals. In the second example, the author’s text uses emotive words and narratives and is based on an imaginary dialogue guided by an ecological perspective. The principle of the imaginary dialogue provides answers to questions the author presumes the reader wants to pose.

Example 1 is a prototypical taxonomy and demonstrates how categories based on professional classification practices can be a helpful tool in research. They can however also function as obstacles in the process of communicating with people who do not have a professional knowledge of anatomy and natural science. Example 2, in contrast, goes beyond a strict taxonomy. The description of the giraffe’s height sounds like a Guinness Book of World Records entry and the narrative about the waterhole dramatises the situation when it describes how the world’s tallest animal gets into trouble because of its long neck and legs.

Education traditionally promotes examples like the second one, employing dialogical texts to dissemination information. The underlying motive for pointing this out is that two key aspects are contained in one text, namely the use of various and more complex categories easily linked to daily life and the use of narratives to reinforce this connection to daily life.

While this may be true, it cannot be a universal claim that everyone will learn from this kind of information solely because of the categories and the narrative form employed. The Danish media researcher Anker Brink Lund presented a fruitful development in how users, readers, visitors and target-groups are viewed by expanding our understanding of age, educational background, lifestyle and ethnicity by focusing on two central aspects, namely if users are interested in and/or affected by the communication presented to them (Lund 1986:33). By crossing two categories with the objective and subjective requirements, the discussion of the user can be split into a four-field model that includes: the engaged, which is someone who is both affected by the actual issue and thinks that it is important; the worried, which is someone who is not personally affected by the issue but believes on everybody’s behalf that it is a problem; the unengaged, which is someone who is objectively affected by the issue but does not think it is the most important one; and the uninterested, which is someone who is neither affected by the issue nor thinks that it is important to do something about.

Take the case of kindergartens, which is a topic routinely covered by newspapers, radio and the local media. Information is regularly provided about kindergartens, the physical condition of the facilities, staffing ratios and accidents. There are two groups of people who should be particularly interested, the responsible authorities - and the parents who have children in kindergarten. Directly affected by conditions in the kindergarten, both groups have an objective need for information about kindergartens, but having an objective need is not enough. They are affected by the conditions, but they do not need to experience that they need more information. They need to know more than just the fact that problems exist, they need to know about problems they personally perceive as important (Ingemann 1990:284-285).

If people cannot relate to the information personally and have no objective interest, like in the case of the uninterested, then they will be beyond the reach of the information museums and exhibitions provide. Even the presence of a lucky coherence of objective interest and subjective affection does not guarantee successful communication. Relevance can be gained by using categories that relate to and interfere with the user’s lifeworld and that need to be discursively constructed close to their knowledge, values, emotions and opportunities for action (for more about the Attention Model see chapter 7).

Circles and dialogue

Nowadays words like user involvement, dialogue, interaction and user-generated content float in the air in the field of museums, reflecting an interest in trying to be more open to user knowledge, values and emotions and trying to think about how users can be involved physically. This focus is based on an initiative that did not come out of nowhere. Specific goals, energy and motivation are necessary to invest in a project. An exhibition could be made by anyone anywhere if the definition of an exhibition is “– an exhibition is what someone calls an exhibition!” [1]. This statement is discursive and open to user-generated content based on the user/producer’s own choices.

It makes a difference whether an exhibition takes place on the street or at a local library, in a huge national museum or in the dining room of a private home. Multiple circumstances influence an exhibition and the communication and dissemination needed. All of these considerations can be summarised in a communication model that goes beyond traditional thinking comprising a unidirectional flow of information to encompass flow-oriented communication. The most important statement in a well-known book on planned communication is that, “There is nothing so practical as a good theory”, as Kurt Lewin once wrote (Windahl, Signitzer & Olson 1992).

Dissemination can be planned and not grow solely out of the objects an organisation collects. Based on pragmatic theory, the model for planned communication, the Circle Model, focuses on the numerous relations that need to be clarified to support the creative process to develop a message in a certain medium. Concretisation, experimenting and formulation lead to the creation of a well-argued, explicit communication plan and a well-founded media product (Ingemann 2003).

The aim of the model is to create an overview of the complex relations at stake when dealing with designing communication on a conscious level. Working intuitively through the elements in the model is possible, but working only intuitively makes it difficult to communicate to other people in the project group or organisation. The model ensures being explicit about making choices, which in turn makes it possible to use the model as a foundation when what is to be communicated is presented to other people.

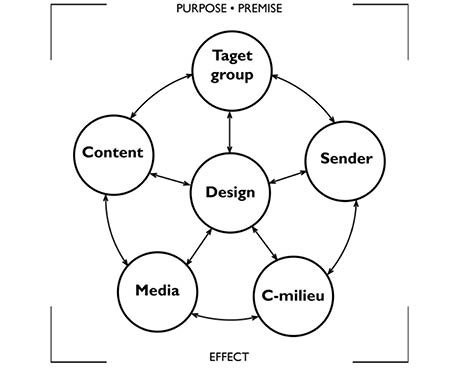

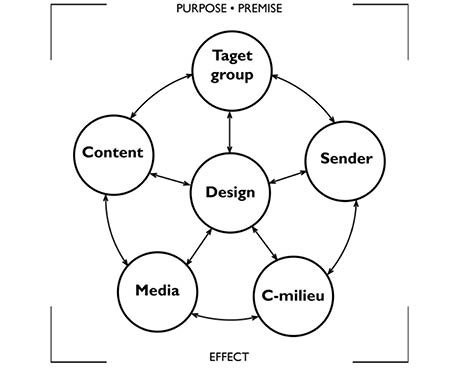

Ill. 19.1: The Circle Model (Ingemann 2003).

Using the Circle Model

This communication model comprises six interdependent circles that influence one another, which is an indication of how dynamic the model is. When the problem area is clarified in one, two and three circles, then decisions made must be looked at again and changed. The model is a running plan that is not complete until the exhibition (or other media product) is complete. Three circles, target group, sender and content, are closely related and serve as the foundation of the entire working process.

From the museum perspective it is obvious and almost natural that the content in the form of objects is the core of a museum exhibit. It is important however to see the content of the communication as more than just objects and professional categories. It must be seen as broader issues that relate to society and to the lifeworld of the exhibition visitor/user. This means that how the content is experienced must contribute with both new and well-known knowledge.

The target group (visitor/user), which is the most crucial element of the model, must be determined based on theories about lifestyle, age, relevance and affection. Uncovering the knowledge and attitudes of the target group about the topic to be communicated is necessary. Constructing a clear, specific image of the visitor and the visitor experience is important for the producer. A model reader who has e.g. competences, linguistic accomplishments, lexical knowledge, personal and political attitudes and values and experiences with various media will be consciously or unconsciously inscribed into the text, which can be comprised of objects, visuals, soundtracks, screens etc. Personal biases, research and contact with the target group mean that constructing a model user to govern creative work is necessary and important (Ingemann 2003:122).

All content and messages have a sender. The organisation or institution is the formal sender of the message and over time the sender constructs an image that the receiver reacts to. Do visitors feel this image expresses trustworthiness and knowledge or does the receiver feel mistrust and scepticism toward the sender? The sender can also be limited to for example a museum curator. The sender constructs an image of her/himself through the content and the expressive and narrative choices. In the eyes of the receiver, one can appear as either authoritative or as an equal.

To be useful in the creative process of creating content and form for what is to be communicated in and around an exhibition, having a rather clear image of the elements involved is necessary. So we are talking about the form of the experience for the target group, the sender and the content as seen from the point of view of the visitor or receiver, but even the institution has a goal and purpose regarding the entirety of what is being communicated.

The next two circles, media and communication milieu (C milieu), are also closely related and expand one’s options. The media are exposed on a specific site and the C milieu is influenced by many other communication channels at the site. More importantly, the C milieu is influenced by a large amount of information about the same or contiguous topics in society that create a breeding ground or resistance to the new communication.

The media in the exhibition site are not given beforehand and the visitor has no fixed understanding of what an exhibition is, should or could be. An exhibition does not have one format and depends on e.g. not only the simplicity or complexity of the content but also on the ability of the conglomeration of media (e.g. visuals, sound, participation, text, odour) to be supportive of the content to be expressed.

At the centre of the Circle Model is design and all the other circles radiate from this point, summarising the outcome of the analysis and decisions made. Design is the phase where content and form are united into a semiosis. Danish researchers Camilla Mordhorst and Kitte Wagner Nielsen call the relation the semantics of the form, as inspired by German researcher Peter Szondi, who believes that the form is settled content (Szondi 1959:9). Mordhorst and Nielsen’s book on cultural history exhibitions concludes by reflecting on form:

As long as the form is given and not the object of reflection, the curators will be bound by its content. All exhibitions will be based on an evolutionary line of thought that reduces the past to the present in an embryonic phase. They will have human being as the absolute reference point and all the objects will primarily be illustrations of the history of civilisation. They will take their departure from an ideal of objectivity that claims that history can be described objectively, the curator’s interpretive presence unheeded. They will take the delimitation of the nation state literally and even the sovereignty of the nation state can be questioned. Finally they will lecture and overlook that the history cannot be presented unequivocally and uncritically (1999:100).

Design is not just designing without meeting the challenge of the content, and as Mordhorst and Nielsen say, the premise is “… that a form always contains content. This means that the form cannot state any content, because the form itself carries content” (1999:3).

The purpose and effect of the communication frames the six circles in the model. The Circle Model requires a succinct formulation of what is to be communicated as well as a clear articulation of the experience the user is to leave the exhibition with.

The Circle Model is an open concept that has room for user input, but it requires users to fill in the simple list of questions with the rich, fluid and exiting content that has to be given an adequate and inspiring form that promotes the development of the communication with visitors.

From the visitor’s point-of-view the considerations taken by the curators, communicators, museum professionals and designers are invisible because the communication plan is not communicated to them, just the final exhibition, where the visitors are met by the museum. In this meeting is when the rejection or acceptance of the exhibition takes place. The museum can open its arms and take visitors seriously by giving them the feeling that the museum wants to understand them and wants to meet them with the right amount of stimulation, understanding, surprises and new challenges. In her inspiring book, The Participatory Museum, designer Nina Simon emphasises that, “People use the institution as meeting grounds for dialogue around the content presented. Instead of being ‘about’ something or ‘for’ someone, participatory institutions are created and managed ‘with’ visitors” (2010:iii).

She also asks how participation works and finds that there are two counter-intuitive design principles at the heart of successful participatory projects:

First, participants thrive on constraints, not open-ended opportunities for self-expression. And second, to collaborate confidently with strangers, participants need to engage through personal, not social, entry points. These design principles are both based on the concept of scaffolding. Constraints help scaffold creative experiences. Personal entry points scaffold social experiences. Together, these principles set the stage for visitors to feel confident participating in creative work with strangers (Simon 2010:22).

As Simon mentions, participatory techniques are an additional option in the culture professional’s toolbox and must, as the Circle Model indicates, besides being part of the experience visitors are to have, be planned ahead of time by professionals able to provide the crucial scaffolding and design.

Openings - Category, objects and communication comprises five chapters that variously look at these central concepts without providing patent answers about how to do exhibitions that are more open and inclusive. The questions discussed are intended to form a basis for promoting greater use of communication and design-oriented practices for exhibitions on site.

Chapter 20 – Museum: The three monkeys – A fluid category

This chapter examines how the see-no-evil, hear-no-evil, speak-no-evil monkeys are used in various communicative contexts and with quite different purposes. The historical background is outlined, but the key point is that the three monkeys do not have a specific form. They are a flexible conceptual idea that works as a highly fluid metaphor. Focusing on this material but simultaneously un-material imagery has caused me to suffer from collector’s syndrome. I ended up gathering so many examples of the three monkeys that I finally had to make a museum, albeit a small on-line one called, Museum: The three monkeys.

Chapter 21 - Object images and material culture – The construction of authenticity and meaning

Objects from daily life can be seen as tokens of culture and society but often they end up as garbage. What decides whether an object stays defined as rubbish or whether it is elevated to the category of valuable object filled with authenticity and meaning? How does this transformation take place and why do the majority of objects remain relegated to the dark shadows of oblivion? Objects from daily life can tell a story and telling the story contributes to creating meaning.

Chapter 22 - Ten theses on the museum in society

Based on the premise that individual exhibitions are more than just exhibitions and in order to open up for a broader understanding and basis for discussion, I wrote almost ten years ago ten theses on the museum in society. Today, if I were to revise these theses I would also focus on participatory museum tools. The overall contribution of the ten statements was to clarify and open a new field of discussion that centred more closely not only on visitors and users but on the communication necessary to establish the museum as an essential part of society and to addresses topics of societal interest.

Chapter 23 – Non-art and self-creation in the art gallery

At art galleries young new visitors are of course met by the art, but also communication about the art in the form of labels, text, folders etc. This chapter focuses on three main areas: how this communication defines the visitor as a somewhat passive recipient of information; how the visitor performatively involves herself to construct her identity using the exhibition and the artist as part of the creation of identity; and how the visitor creates communication in the art gallery. This leads to a discussion of the conflict that arises between curators and visitors as well as a presentation of ten dilemmas to be addressed and resolved in the context of the art gallery.

Chapter 24 – Ten dilemmas professionals face

As a result qualitative reception studies of cultural communication with more that sixty people and in the use of various media, it has been possible to synthesise good advices to be used by the designer as well as the learner/user to generate experiences, meaning making and interaction and to create cues for change in a visual event like the exhibition in any form. The standpoint here comes from the perspective of the person-in-situation. Transforming this view and understanding into the perspective of the producer or organiser reveals ten pieces of advice or fields that need to be considered as dilemmas.

Notes

[1] See chapter 14, the introduction to Invisibles – The exhibition design process. |