Introduction to the theme:

Invisibles – The exhibition design process

At this point we are getting close to a troublesome yet intense field of creativity and research. The epistemological interest is to unveil the subtle processes that take place when information, objects or moods have to be formulated, presented and communicated to an audience. This is the moment of the creation of concepts and ideas in a specific context and, sometimes, at a specific site. In order to get as deeply into the mind and processes of designers and media artists as possible, I examine their processes by following one person and his relation to colleagues, clients, collaborators and the audience in the exhibition and museum context.

Four exemplary processes have been chosen that reveal different aspects of the creative process as well as show the various kinds of challenging situations and decisions that the case person regularly faces. The four processes examined are: 1) the visualisation process of a an exhibition poster for public libraries on the complex and controversial topic of biotechnology; 2) the organisational conflict in a large museum reopening with a thematic exhibition for which the exhibition poster is the turning point; 3) the introduction of a poetic and artistic interpretation into a cultural and historical museum presenting ethnographic material in new media format; 4) an opportunity for the media artist to re-formulate and re-create the memory of people and landscapes over more than three hundred years in drifting sand.

The delimitation of the field

My analysis begins by looking at a recent experience I had at the Museum of Copenhagen, which was going to do a thematic exhibition entitled ‘Becoming a Copenhagener’, that brought back many old memories. The museum’s curator had gotten wind of the fact that I had been part of a group of enthusiastic young activists who had made a 16 mm documentary film in the summer of 1972 on 69 Gipsies living on the outskirts of Copenhagen in the Amager Common, a former dumping ground. In the 1970s the area was unused, but was equipped with a single water pump. The Gipsies, or Romany as they were known as at the time, had placed their caravans on the Common. The museum’s introduction to the thematic exhibition states:

The special exhibition focuses on immigration to Copenhagen, as the catalyst of, and pre-condition for, the town's growth and change. The physical traces left by the citizens of Copenhagen in former times, the urbanisation process and immigration are particularly interesting. Immigration is, and always has been, an important factor in the history of the capital. Not just as a curious feature in the life of the town, but rather as a key ingredient in the town's growth and development. While Copenhagen probably would not exist today had it not been for the continuous stream of immigrants that contributed to its development down through history, it most definitely would not have become the metropolis with which we are familiar today without their contribution [1].

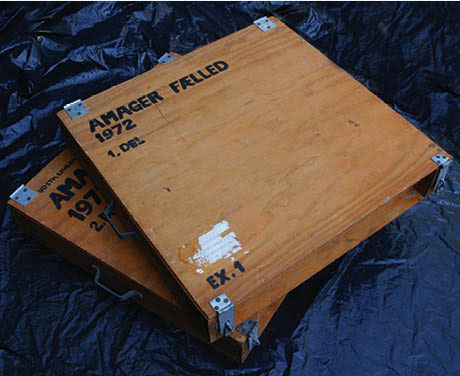

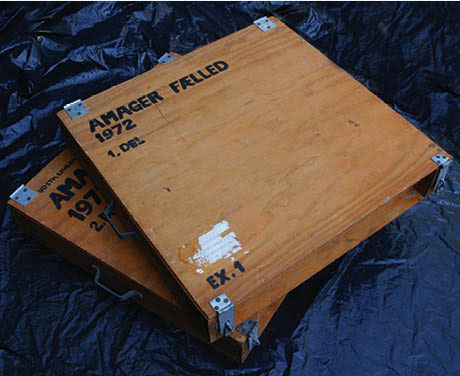

When asked whether the film could be used in the exhibition at the Museum of Copenhagen, I realised that I might still have material from the original exhibition in my cellar. Fortunately, my cellar still held two specially designed wooden transportation boxes containing 20 black chipboards. They had remained unopened since being placed there in perhaps 1974 when the temporary exhibition was taken out of circulation after having been presented at forty libraries across Denmark over a period of two years [Ill. 14.1].

Ill. 14.1: The two wooden boxes used to transport the 20 black chipboards with black and white photographs and text to the 40 different libraries.

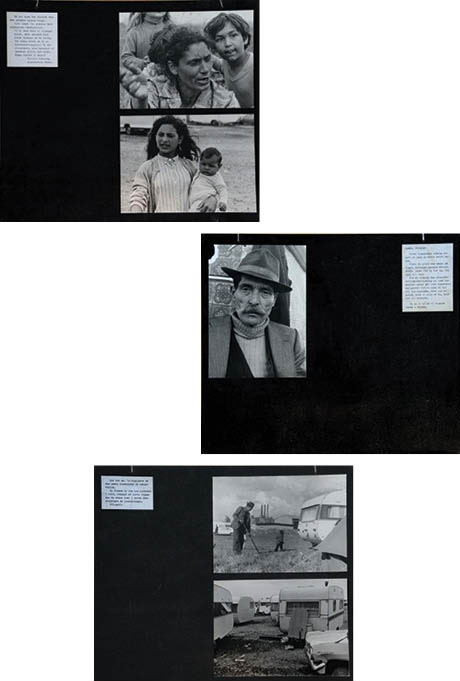

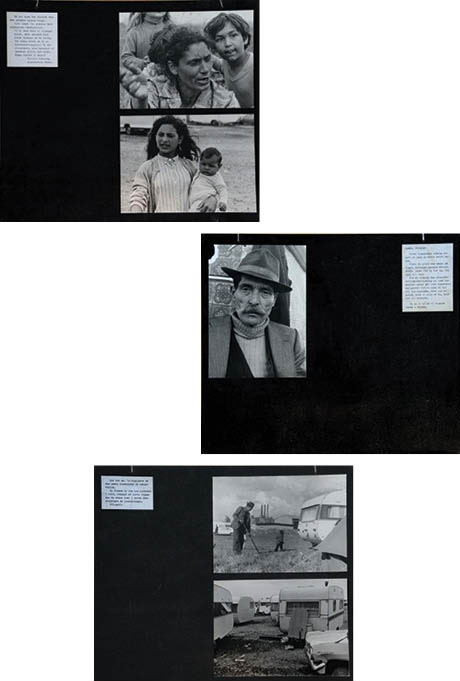

The motif for the original exhibition was the Amager Common and the life of the Gipsies that revolved around the water pump there in the summer of 1972. Made up of black and white photos, the exhibition also contained various texts, some were written by the activist group and others were photocopies taken from newspapers [2].

Made up of four people, the activist group’s motivation was its empathic understanding of and desire to support the Gypsies, who found themselves in a tight corner. The activists’ shear enthusiasm was also one of the main driving forces behind their creative process.

In a document found in the archive there is a three-page explanation describing the basis for the entire project. The archive also contained a documentary film produced in 1972 called Amager Common 1972. In addition to the material for the travelling exhibition, there was a presentation of a large public political meeting at the Danish National Museum where more than 500 people discussed various cultural, humanitarian and integration issues involving the gipsies. The goal of the four young activists states:

The primary intention with our work was to prevent the Gipsies from being chased out of the country ... We tried to show the empathy we feel toward the Gypsies and their complex situation. Our aim is not to express our own view of their circumstance, but to help them bring forward their own wishes, thoughts and ideas. To the Danes, we also part of what is happening. We wanted to try to remedy the misconceptions that existed about the gypsies that we had had or that we had run into. In other words, we wanted to change attitudes that chiefly were influenced by our lack of knowledge about their culture and ways of living (Documentation 1974).

In the context of the new exhibition nearly forty years after the original documentary film was made, the exhibition, the political meeting and the various elements from the historical event are presented in the context of a theme called, ‘Wanted unwanted’. [Ill. 14.2]

Ill. 14.2: From the Museum of Copenhagen 2010 exhibition: On the left the film Amager Common 1972 is being shown on the wall. In the middle are six black chipboards. Below the chipboard farthest to the right in the second row is a yellow Ill. 14.2: From the Museum of Copenhagen 2010 exhibition: On the left the film Amager Common 1972 is being shown on the wall. In the middle are six black chipboards. Below the chipboard farthest to the right in the second row is a yellow

poster, partially obscured by a little boy’s head, for the political meeting and panel debate. poster, partially obscured by a little boy’s head, for the political meeting and panel debate.

On the left on the wall a five-minute excerpt from the film Amager Common 1972 is being shown. In the middle of the photo there are six black chipboards with black and white photographs, typed text and photocopies of newspaper articles. Partially obscured by a little boy’s head is a yellow poster advertising the political meeting and panel debate at the National Museum of Denmark.

Incredibly, the work of four young activists aged 20 to 27 who had cooperated closely on all aspects of producing a documentary film was now on display almost forty years later. Their enthusiasm and commitment to making the film and the exhibition are still evident.

In the context of the museum exhibit three important aspects of the story of the 69 Gipsies appear.

First, there is the concrete story of the rejection and later acceptance of the group of the Gipsies in 1972, the main issue that motivated three young male and one female activist to explore the matter and in the process make a film and an exhibition as well as spark a discussion. The second aspect was one’s common civic duty to take care of people who need help and support to be treated as citizens. The third aspect is the actual media products, i.e. the film, the exhibition text and the overall visual appearance not to mention the argumentative manner tone employed and the general way of talking and creating a discourse in the 1970s. To be complete, a fourth aspect must also be taken into consideration and that is how a contemporary context reflects the 1970s but also dares to influence the discourse and attitudes in the Danish society today, which comprises groups with highly xenophobic opinions as well as a political system with a dismissive attitude.

The experience of having something I helped create become part of a museum exhibition underlines the many internal and external circumstances that influence the goal of this chapter, which is to show what the “invisibles” in the exhibition design process are, as indicated by the title of the chapter. It seems that the topic, the objects, the people interacting, the discourse, the ambiance, the … you name it … all influence the creative process. Fascinated and preoccupied with these processes, my aim is to get very close to them. I want to get inside the processes and articulate what is perhaps nearly impossible to narrate or follow in detail.

When Sharon MacDonald began studying the Science Museum in London 1988 she wanted to go behind the scenes and track the history of a particular exhibition in order to take her audience into the world of the museum curator and to show in vivid detail how exhibitions are created and how public culture is produced. MacDonald wanted to answer questions such as:

What goes on behind closed doors at museums? How are decisions about exhibitions made and who, or what, really makes them? Why are certain objects and styles of display chosen whilst others are rejected, and what factors influence how museum exhibitions are produced and experienced? (2002).

MacDonald observed the creation of a major permanent exhibition in the Science Museum in London on a day-to-day basis for a year before its opening in October 1989 (MacDonald 1996). In her brilliant ethnographic study of the making of Food for Thought, she explains that she tagged: “… along with the team [of six women, none of whom were subject experts, which was seen as a strength], scribbling my notes in a corner, asking questions, … [I] studied the stacks of paperwork that had accumulated in the ‘Food’ offices, attended exhibitions-relevant meetings elsewhere in the museum, and interviewed staff in the Science Museum …” (MacDonald 1996:157).

The outcome of the material she collected was important but also frustrating because the goal of the people behind the exhibition was to create something completely new that contrasted with the traditions otherwise followed at the Science Museum at that time: In contrast to those exhibitions which were written for curators rather than visitors, exhibitions which were said to ‘go over people’s heads’, Food for Thought was to be ‘accessible’ and ‘user-friendly’ (MacDonald 1996:159).

MacDonald shows how this goal drove team members but also how they were sometimes blocked by the organisation and by the Museum’s director, who worked to move the team’s focus away from the social, political and historical aspects of the exhibition’s theme. MacDonald writes that the, “… focus almost exclusively upon technological aspects of production was justified, albeit with misgivings from some team members, with the statement: ‘we are the Science Museum after all’ (1996:163).

She stress that pre-existing definitions of science and of the perceived roles of the Science Museum were continued in this new and challenging exhibition and that it “… seemed like an exhibition less different from previous ones than talk during its making had led me to imagine” (1996:164).

In many ways I share her interests and questions concerning what, how and why certain factors influence how exhibitions are produced, but my focus and interests differ from MacDonald’s in two respects. First, MacDonald focuses on museum exhibitions and I want to go beyond the museum and into a broader use of exhibitions on other kinds of sites. The exhibitions could be theme driven, enthusiasm driven, aesthetically driven, research driven or politically driven and placed in libraries, city halls, on the streets, in workplaces, in the open air along a stream, in experience centers or, last but not least, even a museum.

The exhibition MacDonald studied was 810m2 and had a budget of £ 1.2 million. In the context of the Science Museum this also led her to focus on the internal organisational conflicts that influenced the production of the exhibition. My interest is different. I narrow the perspective down to small exhibitions or minor parts of larger exhibitions. For example, when I analyse the creative production process I look at a small poster exhibition on biotechnology for libraries and in another case I look at the making of a multi-screen show that is a minor part of an experience centre.

In contrast to MacDonald, who follows an entire team daily for over a year on a day-to-day basis, I had to come up with a more sophisticated concept for the research process. The most important part of the concept involves following one person in the production process in order to get close to the creative process as it happens in real time. The questions of what, how and why do not focus on the overall organisation or team, but centre more narrowly on how people get their ideas and concepts and how these ideas and concepts enter into the world as words, sketches, photographs, documents, timelines, notebooks or whatever physical form the invisible process ends up being consolidate into and expressed in.

Following someone this closely is almost impossible because the process can take place over seconds, minutes, hours, weeks, months or even years – and in many places, e.g. in the workshop, on a train, in the bath, at meetings, in bed, on a walk in town or in the woods, while swimming etc. (Csikszentmihalyi 1996).

The only person you are close to one-hundred percent of the time everywhere is yourself. If you want to follow the processual experience in a sort of reflection-in-action you have to be open to introspection. As a result, I have chosen to do an introspective analysis in the tradition of phenomenology, experimental psychology and semiotic sign theory as found in Ronald Barthes’ work, who, in his autobiography, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, turned towards himself as a text to be studied. Developing methods designed to allow close examination of actual practice can lead to an upgrade of the practice-learned insights to a level where tacit knowledge is revealed (Polanyi 1967). Consequently, research in creative processes becomes more vivid and more related to actual practice, in addition to developing approaches for opening the black box of design processes.

Introspection is not easy. When you create something you are in a flow or state of contemplation as a vivid living person who is making an attempt to be unaffected and undisturbed by arbitrary phone calls, meetings or mails (Csikszentmihalyi 1996:120). But the most annoying disturbances and dissonance come from the creative person himself. Being in the flow and in contemplation can be disturbed by switching from a creative, constructive mode to an analytical and more rational one. When Donald Schön was working on developing his theory of reflection-in-action his goal was to follow the creative processes and to solve the problem of switching between various modes. In his wonderful book, The Reflective Practitioner, Schön ends up following a teaching or supervising situation where someone who is not so experienced meets someone who is.

Teaching or supervising

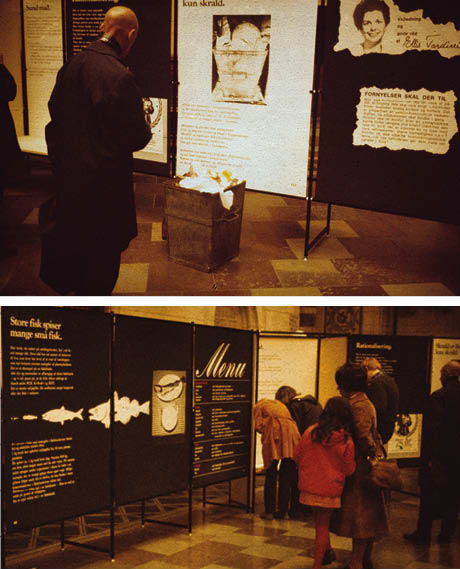

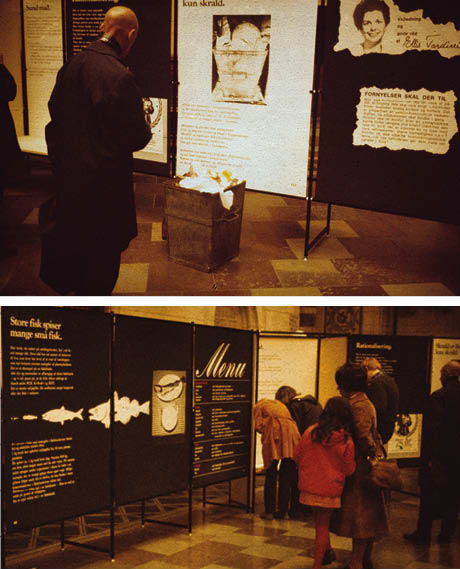

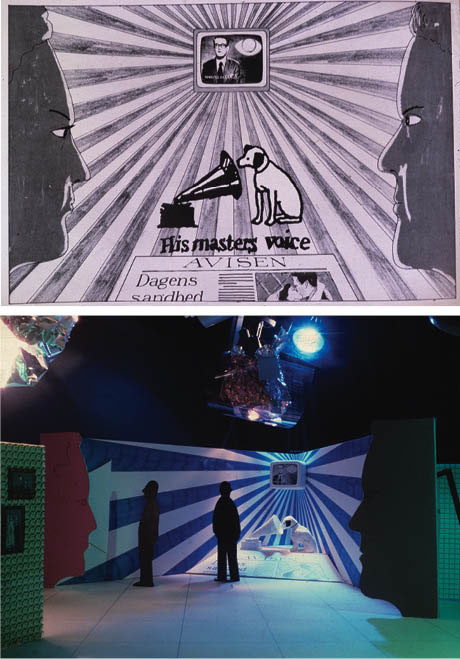

In the early 1970s, working as an art director and graphic designer, I became deeply engaged in the growing environmental movement in Denmark. The group, called NOAH (after the Biblical figure), consisted of many young people with specialist knowledge. Although I did not have expert knowledge on environmental issues, I contributed to the group with my professional knowledge about communication and design. Our collaboration lasted eight years and one of our most important, time-consuming endeavours was an exhibition. After nine months of preparation, the work of fifty people resulted in the opening of a huge exhibition in the Copenhagen town hall in September 1970 entitled “Some information about the earth we all live on”. It was an epoch-making event on various levels as the exhibition marked a growing interest in the issues surrounding consumption, growth and quality of life. The work put into the exhibition from a communication and design perspective was significant in that it elevated the generally casual, unprofessional design and lack of consideration for communication in grassroots organisations to a higher level. [Ill. 14.3].

Ill. 14.3: The NOAH exhibition »Some information about the earth we all live on« presented in the Copenhagen town hall in September 1970. The exhibition was later made into a travelling addition used for educational purposes in Danish schools. Ill. 14.3: The NOAH exhibition »Some information about the earth we all live on« presented in the Copenhagen town hall in September 1970. The exhibition was later made into a travelling addition used for educational purposes in Danish schools.

The exhibition shows that alternative experts have a strong voice. The exhibition shows that alternative experts have a strong voice.

The work process behind establishing this exhibition (and the accompanying book) was a learning-in-situation process in which I as the communication and design professional trained experts in other fields to become better writers (in popularising the often difficult content with respect to substance), better visualisers (to consider lexi-visual communication more, i.e. the word/image relation), better storytellers (to find the angle or framework of the story) and better deliverers (keep within deadlines and accept revisions made by the small communication and dissemination group).

My interest in and work with NOAH led me into teaching small courses and supervising other grassroots groups at architecture schools and at universities. The focal point was the transformation of knowledge produced by subject matter experts into communication understandable by lay people. Along with my continuing career as a graphic designer and media artist I became more and more closely associated with communication studies at Roskilde University and expanded and systemised my experiences about exhibitions and ended up writing a book called, The Exhibition Handbook: About technique, aesthetics and narrative modes (1986).

Although unfamiliar with Schön’s work at the time, this book also follows the learning process between the not so experienced and the experienced. Education, supervision and authoring are one way of getting closer to the fragile creative process. In the dissemination the whole process of producing, an exhibition has to be taken out in the light, exposed and explained.

The most powerful statement in my book is that, “[A]n exhibition is what someone calls an exhibition!” (Ingemann 1986:7). This statement is provoking and offers a starting point in which an exhibition is not a collection of objects but an urgent or critical issue that must be taken into the public sphere and be confronted.

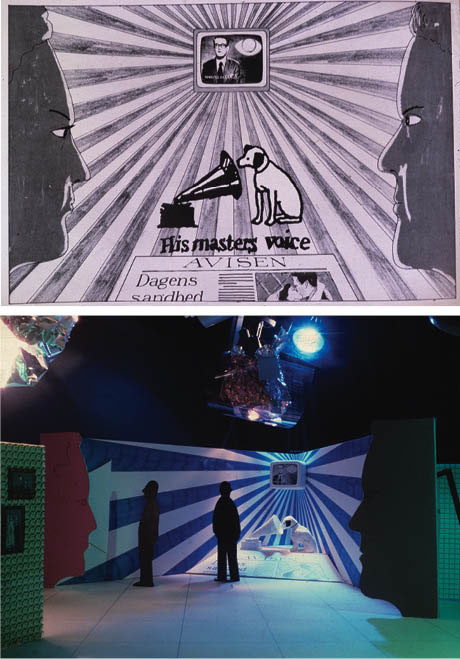

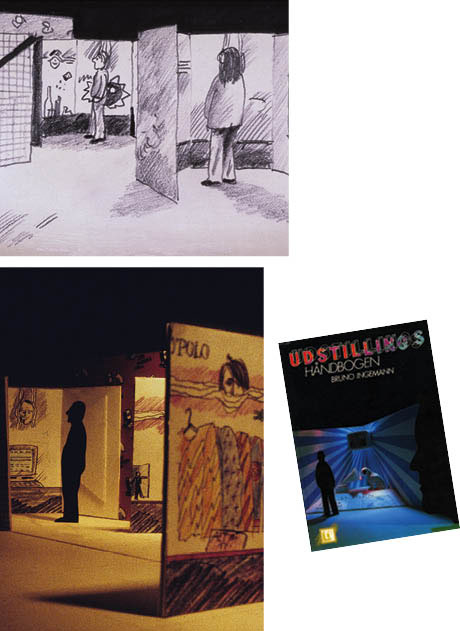

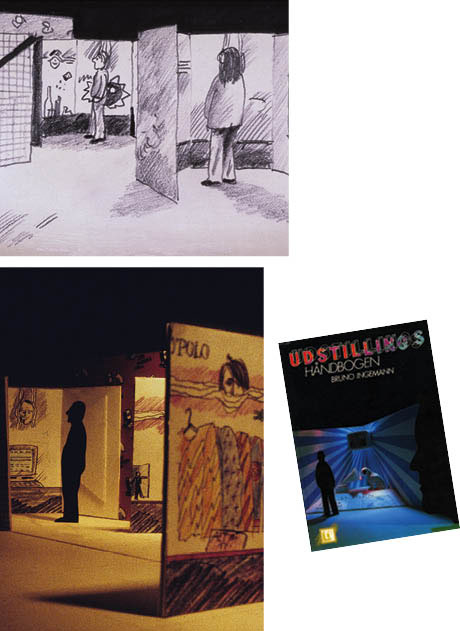

Ill. 14.4: The playful idea created for the book and for discussing various approaches to the development of ideas and design. Illustrations from the book. Ill. 14.4: The playful idea created for the book and for discussing various approaches to the development of ideas and design. Illustrations from the book.

For the book I did a new exhibition about how the media has influenced the daily life of ordinary people from 1900-1960. This theme was introduced to make it possible for the author to enter into dialogue with the various considerations and possible concepts to be rejected, chosen and used. I oscillated between being the person who was experiencing the situation and the person who put it into practice. This is the most important concept for getting in touch with the narrative in an exhibition and how the creative phases are brought into play.

The tone of the book is personal and the language rather informal as is the case, for example in the book’s preface (Ingemann 1986:4):

I want to make you more conscious about facing what you really experience when you go to an exhibition. I will try to introduce some terms about what you see and hear so you can be more aware of the media. And the experience.

Not only to sharpen your senses and become more conscious. No, I want something more.

The experience you have as the spectator of others’ exhibitions can be used for something. You can also use it when you make an exhibition. It is precisely when you yourself become productive that you seriously look and experience.

The concept of reception/production is rather fruitful regarding supervision and making the designer and author aware of the complexity of the impulses, considerations, emotions and decisions involved in the development of an idea as a mixture of topic, form and whatever resources are available (Ingemann 1986:84). Getting even closer to the invisible design processes must however be possible.

One-in-one: introspection and re-enactment

From 1990-1991 I was in a transition period between being a designer and taking on a new role as a PhD candidate. Although not lost in the transition, I faced a challenging but at times also burdensome and counterproductive situation in which I oscillated between being a designer and being an academic. In the midst of this fractured existence I was invited to do an exhibition for an organisation called the Technological Board, which had been appointed by the Danish state to raise issues of a problematic or critical nature about society and technology.

Over the course of more than a year while doing the exhibition I developed a loose idea about doing something on the creative design process. Consequently, I gathered every little scratch of paper jotted with notes and made an accurate dairy of my work process. Yet even with a pile of sketches, rough drafts, texts, layouts in multiple versions and the final poster exhibition I still had no idea of how to get closer to the reflection-in-action that took place that I had hoped for.

The challenging but at times trying transition process I went through helped me create a new approach to heightening the level of introspection. This approach meant establishing and maintaining the two roles I had, one as a designer and the other as a researcher and then letting them freely interact with each other. They are one person but two different roles are preformed. And although there are two roles, one person maintains the various modes of the two roles through the resulting dialogue that takes place over time and in writing but not in talk.

This concept on the introspection of the designer/researcher developed slowly over the years, the pace of development hampered by a lack of time as I was occupied with other interesting duties and projects that prevented me from paying attention as a researcher to the more creative mode I still practice.

These duties and projects involved for example participating in doing the re-opening exhibition at the National Museum of Denmark in 1992 and creating a totally new nature centre in northern Denmark in 1998.

As a researcher I may not have had time to further develop the introspection concept, but I had also changed roles again. I had thought of myself as a graphic designer for many years, but I was in reality beginning to take on a more open role and was becoming something of a media artist.

A couple of years after the exhibitions were over, I knew that I wanted to write an article about the introspection concept, but I abandoned it again because I was still unable to grasp the important aspects of reflection-in-action and what the most influential factors are.

Confronting the rich amount of material available from the two previously mentioned exhibitions after a long time gap, I feel like a stranger looking at the material and the processes. More than twelve to fourteen years have passed since the processes took place, so talking about myself, the designer and media artist, in the third person instead of the first person is the approach I will take in the next part of my analysis..

Ingemann’s true goal is to maintain a distance but to use an introspective method to open up his memories like one would open up a black box. It is the nature of exhibitions to disappear because they are made for a specific site at a specific time, have an ‘opening’ period of days, months or years and then the exhibition only exists in the form of documents such as texts, photographs and videos. This time the media designer/researcher wanted to get closer to the creative processes and so he constructed a dichotomy of closeness/distance.

It was coincidence that he came across a surprising and powerful way to access hidden emotions and knowledge as a means of creating the desired closeness and level of introspection. Because the exhibitions no longer exist he tried to reconstruct part of one of them by building small-scale models of an exhibition room. He also reconstructed the entire narrative and visual aspects in a slide show about the Shaman and a complicated multi-screen show about the history of drifting sand. He found the original poster for the ”Journey” exhibition and he also found the original slides with the images used digital manipulation was possible, thus allowing him to re-enact the process.

Originally believing that he was embarking on a reconstruction process, he realises that he is actually engaging in a re-enactment process. Employing a method that involves re-enactment allows for a different, deeper kind of access to one’s memory than images and text documents do. It also comprises physical involvement, participation and immersion. Photo therapist Rose Martin’s view of the body as performing supports using a re-enactment approach: “The body must be regarded as a site of social, political, cultural and geographical inscriptions, production or constitution. The body is … itself a cultural product” (2001).

Performing the re-enactment process by reconstructing the models and the visuals provided numerous clues for retrieving his memories. The re-construction and the re-enactment processes blended together into a new re-creative process. The models and the visuals were re-created as close to the original exhibition as possible. During the re-construction process the material and the goal turned out to have a dual edge in that the material could be used for communicating about the projects and it could be used to go through a re-enactment process comprising physical involvement and participation that automatically involve immersion in the process. Culture theorist Annette Kuhn stresses that, “…memory is an active production of meanings… once voiced… memory is shaped by secondary revision” (2002:161).

The exhibition in progress and research

The activist project about a film, exhibition and event on the former dumping ground called Amager Common, and the Gipsies who temporarily settled there, reflects the activists’ enthusiastic involvement in the issues surrounding the Gipsies and their strong commitment to them. The activists also had a greener approach to filmmaking and the design processes.

The fact that the original exhibition had become part of a museum exhibition underlines the many internal and external circumstances that influence what Ingemann calls ”the invisible exhibition design process”. The Amager Commons example represents a common way of doing an exhibition, namely by finding and taking objects from various situation, events and sites and placing them in a room and calling it an exhibition.

This is in contrast to the traditional approach that Ingemann calls “research as exhibition” or a transvisual analysis. From the beginning that kind of projects were located at a specific site and the end goal was an exhibition. The design and production methods were used as the creative means for involving reflection-in-action. The binary opposition of closeness/distance became osmotic and introspection and creation became part of the time and site of the project. One of the projects within this framework is presented in Chapter 13, which demonstrates how focusing on the performative from the beginning of a process pushes the invisible processes into becoming more visible by shaping one’s memory and by creating what Kuhn describes as a secondary revision.

Chapter 15: Provoked dialogue as reflection-in-action in designing an exhibition

The focus of this article is a case that involves the communication of rather complex content about biotechnology, or more precisely, it is about the development of the design process over the course of more than a year. The client was an organisation called the Technological Board, appointed by the Danish state to raise issues of a problematic or critical nature about society. In this context the purpose was to examine and define what the core issues in the debate on biotechnology are about. These expansive issues were then to be communicated via a small poster exhibition at public libraries.

The process concluded in September 1990 and the subsequent dialogue was written during the following year [3]. As luck would have it, time and circumstances coalesced in such a manner that the researcher, who has nearly twenty-five years of practical experience, was at a crossroads that meant the possibility of combining his experience with graphic design practice and the writing of his dissertation at the same time as the making of the exhibition. The case in question was developed in this context, the uncertainty and openness of the situation providing fertile soil for coming up with the idea of gaining insight into the creative process of design. The researcher’s aim is to discover how visual ideas are created. How do creative processes unfold? How are knowledge, insight and experiences facilitated beyond rational logic modes of thinking? What effect does the craft process have on creativity? This dialog is interspersed with narrative reflection from the more detached perspective of writing this chapter.

Chapter 16: >REJSEN< - design between creativity and organization

This chapter looks at the creation of the overall graphic design and the poster for the 1992 opening exhibition, THE JOURNEY, at the National Museum of Denmark from the perspective of the organisation and the designer. On a superficial level the production and approval of the exhibition poster appears to be a simple task, but upon closer scrutiny the process reveals a significant amount about the organisation, the underlying conflicts and the decision-making process. How do things end up going wrong? How can the creative process be so productive? This processes is theoretical elucidate through the organizational researcher Edgar Schein’s three layers of organisation culture and possibilities of change.

Chapter 17: Journey of the soul – From designer to media artist

The general practice of cultural history museums is to treat original objects as sacred and not alter them in any way when they are exhibited. It is acceptable to construct or insert a context to help understand the meaning and value of the object e.g. by adding a linguistic message to anchor the meaning and interpretation. But how can this precondition be overruled or transformed so the use of the original objects can be displaced and accepted? In this chapter the Shaman Tower as part of the exhibition >REJSEN< is analysed and specially the production process of the slideshow for the tower is scrutinized with focus on how original and old crayon-drawings from an Greenlandic artist is allowed to be transformed and interpreted into a new context as it appears in the new re-constructed and re-enacted processes and work of art.

Chapter 18: Drifting sand – the poetic interpretation and the process of construction. The preparation for the unexpected gifts

This chapter is about sand. It is about the story of drifting sand over the course of three hundred years – but it is also about the creative process of sand, drifting sand and the creation of a multi-screen slideshow for a new exhibition. The aim of this chapter is to take stock of the creative process and find innovative ways to address the unexpected gifts arising from meeting resistance to this part of the exhibition’s form and content. Crises arose and led to despair, which in turn led to a new framework, creative answers and renewed energy. By re-construction and re-enacting the site and the multi-media show the media-artist got back to the memory of the days of construction and creation for more that ten years ago and this powerful experience gives insight into the invisible creative design processes.

Notes

[1] 'Becoming a Copenagener´

[2] The film »Amager Common 1972« was made in the Danish Film Institute’s Workshop framework. The film group consisted of Jimmy Andreasen, Niels Arild, Bruno Ingemann and Pia Parby. The exhibition consist of twenty 60 x 70 cm chipboards. Distributed by the Danish Library Association 1973-1974. Jens Frederiksen also became part of the activist group for the exhibition.

[3] The entire project and the final product were analysed in detail and published in an internal stencil as working papers. The Danish title is: Grafisk Design – om de kreative processer, strategier og deres resultat, Papirer om faglig formidling, [Graphic Design: On Creative Processes, Strategies and Their Results] Communication Studies, Roskilde University, 1991.

|