Intro:

Why objects, showcases, exhibitions and museums are so important

Feeling enthusiastic about an exhibition or the objects presented is one way of entering into the realm of art, history and nature at a museum. Wonder is another way. Resonance a third. It is not possible to spend years visiting exhibitions and galleries without being fascinated and feeling “resonance and wonder” as Stephen Greenblatt so aptly puts it (1991:42).

My perspective is not from the point of view of individual museums or museum genres, e.g. art galleries, natural science museums and history museums, and then out into society – but the other way around. I am a human being living in society. I visit many museums with various kinds of exhibitions and am also engaged in other important aspects of human life. Maybe an exhibition can give me something, maybe not. An outside perspective enables me as the visitor, viewer and analyst to maintain a distance to the internal affairs of the museum and to remain an informed visitor, yet nevertheless an ordinary person who wants the museum to be attentive to my needs and who wants to experience or maybe learn something. As the museologist Kenneth Hudson wrote many years ago, “Most visitors to museums are not studying for an examination in zoology, agricultural engineering, anthropology, [or] art history …” (1987:175). Ordinary visitors generally do not subdivide the world into these types of categories.

Present on site

The first part of the title of this book, Present on site, focuses on the concept of visitors being in the present and being aware of centring their attention on the now, not to mention having an open mind and open senses. Present on site also literally means being on site at a museum and an exhibition, where many unusual experiences are possible and often expected to take place. In the field of contemporary art, articles from daily life and ordinary surroundings can be transformed into an open art space. The ambience of streets, gardens, shops, houses and sitting rooms can become part of an exhibition and work as tools for artistic expression. An event that took place in the small rural town of Lejre, Denmark, illustrates this process.

In the summer of 2001 as part of a project called Camp Lejre, the town was invaded for a few weeks by 47 international artists from eight different countries. The town’s 3000 inhabitants were asked if any of them would like to open their homes and gardens as the setting for site-specific art work and then allow these areas to be open to the public for three consecutive weekends, basically turning any volunteers into a mixture of curators, watchmen and owners. More than thirty people accepted the proposal and agreed to let the artists into their homes to create something new. Visitors during the open house weekends were mainly locals curious not just to see the art works, but also one another’s homes. Many people however also came from other cities, especially Copenhagen. This was an extraordinary, exciting event.

One of the artists had two families participate in a project in which objects from one family were moved into the other family’s home and vice versa. The project was called, If you remember, I’ll forget ... Fifty-nine objects from the Westergaard family were placed in the Holbjerg family home and forty-four objects from the Holmbjerg’s were placed at the Westergaard’s.

How was it possible for visitors to know what the premise of this project was? I reside in Lejre and spent a warm, sunny Saturday afternoon navigating my way around the different sites using a map and a pamphlet with project titles with a numbered list of names and addresses of participating families. Most of my information about If you remember, I’ll forget ... came from a woman in the Westergaard family who immediately made clear that all of the paintings and other art objects in her home were from the other family. Pointing out where the other family lived 500 metres away on another street, she explained, “I also feel different. I nearly can’t stand being here!” Later, after I enquired about some small life-like porcelain figurines, she disassociates herself from them by exclaiming, “… all the Royal Porcelain is not ours!”

The Westergaard home with the objects from the Holmbjerg family. Video screendumps. The Westergaard home with the objects from the Holmbjerg family. Video screendumps.

The Holmbjerg home with the objects from the Westergaard family. Video screendumps.

Although curious, we cautiously entered the gardens and homes of people we had never met. Under the cover of the event and the protective presence of other visitors we walked through what was otherwise a private area but what had been transformed into a public space for three weekends in a row. The most important aspect of the experience was the newly acquired perspective or gaze at the ordinary and familiar. Although we had never seen the Westergaard family home before, it was familiar because it resembled many other homes we had visited before. There were tables, chairs, carpets, bookshelves etc. But there was also something new: the pictures and the small figurines. Normally, when visiting a home, these art objects remain relatively unseen as they blend in to create the ambiance and mood of the home. Often they are nearly invisible, unnoticed due to how commonplace they are.

Knowing that the art objects belong to “the others” and are “not ours” increases the inclination to look at them more intensely. The initial, somewhat superficial impression is that the objects seem to fit well into the Westergaard home, so we look more carefully at the paintings. What about their colour and how they fit with the sofa? Or what about the paintings’ expression? Were they too bold and aggressive or too soft and weak? Did the family simply lack a sense of connection and personal history with the paintings?

This reaction and distance to “the others” and our reflections made us eager to visit the other family, the Holmbjergs. Seeing their art objects here made us want to see their normal setting and we were also curious about seeing the Westergaard family’s objects in unaccustomed surroundings. At the Holbjerg’s comments were made about “the others”, but they were also supplemented by personal observations and moments of inspiration. For example, the woman in the family explained, “An owl like this is fabulous. We need to have a glass owl like this – when the sun is low in the sky the light is fantastic”.

The discussion in this home was different not only because the mixture of ten visitors was different but also because of the family’s focus on the fact that their home was being invaded by so many strangers three weekends in a row. The statement, “We need to be home!” stresses the point that their normal family life was also changed by the simple duty of having to be present on site. Due to the openness of the family, visitors discussed their experiences at other sites and with some of the fifty other works of art. They were excited about meeting so many new people and reconnecting with neighbours they had not seen for a long time.

In a book describing the entire project and its individual elements, Camp Lejre, artist Jesper Fabricius describes the concept of exchange behind If you remember, I’ll forget ... and reflects on the whole process:

The difference between the ‘private’ and the ‘general/public’ has been my most essential interest and an incentive in my work If you remember, I’ll forget … When you follow that part of the organiser’s proposal and place art in private homes, you find yourself in a dilemma. Are you in a private space, or has the private space become public? This is, for instance very much the case in the reality shows we see on several TV channels, as well as in the phenomenon where people film themselves in more of less intimate situations in their own homes and put in out on the Internet. My thought was to go in the opposite direction and make a project that would only speak to the two families involved (who very generously let me into their homes). The thought was to swap their pictures and objects of art around between the homes. … For the audience who came to see the exhibition in a private home, the exhibition was … invisible at first sight. Then what happened was - which I hadn’t foreseen, perhaps naively - that the hosts told the visitors about the project, and thus made the invisible visible again (2002:96).

Fabricius is essentially asking, “Is it even art? I don't know.” But seen from the concept of relational aesthetics, as coined by French curator Nicholas Bourriaud, the project’s use of daily objects, social practices and their transformation is part of thinking relationally. Bourriaud basically believes that what we call reality in fact is a simple montage. The aesthetic challenge of contemporary art resides in recomposing that montage: art is an editing table that enables us to realise alternative, temporary versions of reality involving everyday life. The artist de-programmes in order to re-programme, suggesting that there are other possible usages for techniques, tools and spaces at our disposition. He sees artists as facilitators rather than makers and regards art as information exchanged between the artist and the viewers. The tools of the artist are no longer merely canvas, paint, bronze etc. but daily activities like massages, bathing, second-hand shops, serving a meal, interviews, encounters and questionnaires (Bourriaud 1998/2002).

This leads to a question viewers are entitled to ask concerning any aesthetic production: Does this work allow me to enter into a dialogue? Could I exist, and how, in the space it defines? A form is more or less democratic … that is [if it] do[es] not allow the viewer to complete the form (Bourriaud 1998/2002:109). When Bourriaud developed his concept of relational aesthetics it was based on his observations as the curator of artists’ works powering the new tools and their re-programming of daily life and interactions. Fond of going to galleries to look at Rothko and Kandinsky, Warhol and Kosuth, Sherman and Viola, I found that Bourriaud’s texts, including shorter articles I had read more than ten years earlier that later led to his influential book, Relational Aesthetics, gave me a new gaze and a new framework for visual art and its relation to social life in society.

Telling – entering a dialogue

What are the stories to be told? Which kinds of themes or dynamic events in society need to be introduced and exposed in exhibitions? And who is the form and content created for in the attempt to include and allow dialogue?

Suzanne Keene questions the whole idea of the anti-elite exhibition, saying, “Perhaps the responses of museums in developing education and out-reach services is correct: it is the exhibition to be visited that lacks the postmodern flavour” (2006:5). Eilean Hooper-Greenhill contrasts the ‘modernist’ museum with what she terms the ‘post-museum’. The essence of the post-museum involves more of a process or experience than a building to be visited. In it, the role of the exhibitions is to focus a plethora of transient activities – dynamic events within and without the museum (Hooper-Greenhill 2000:152-153).

Exhibitions can have their starting point in e.g. works of art, objects, the timeline of archaeology and art history but can these categories and traditions be animated by focusing on themes and challenges in society? In order to explore the topic of entering into dialogue in more detail, I will discuss vital issues brought up by two prominent museologists, museum director Kenneth Hudsen, author of the book Museums of Influence (1987), and museum director Robert Janes, author of the book Museums in a Troubled World (2009).

I 1987 Hudsen claimed that, “… museums only fully develop their potential for action, when they are actually involved in the major problems of contemporary society” (1987:112). Delving further into the subject by doing a detailed exploration of what the main problems are now and what they will be in the future, he ranks five key issues based on importance:

First, the degradation of the natural environment under the joint onslaught of greed and ignorance. Second, the political, scientific and financial pressure which combine to concentrate enormous, and possibly irresponsible power in the hands of the military machines of the United States ... Third, the truly tragic fact that decolonisation has not worked … in the sense that the world’s former colonial territories are … poorer, more insecure, and worse-governed than in the days when they were controlled by European power. Fourth, that knowledge is becoming increasingly divided and specialised, and increasingly incomprehensible to laymen. This specialisation has extended to art and music, from more and more of which the common man feels himself totally excluded. And, fifth, that persons in positions of power and influence protect themselves by sheltering behind walls of generalisations and vague terminology. The gap between the concrete, the local, the real on the one hand and the prestigious, the theoretical, the national and the international on the other becomes steadily wider (Hudson 1987:173-174).

These five major issues can be further divided into different parts. The last two points about specialisation of knowledge and the gap between people in positions of power and influence and the ‘others’ can easily be connected to museums and exhibitions, which may broaden the gap between who is included and excluded when visiting a museum. The first three points focus on political and financial power. Hudson’s description of the international community is couched in strong words such as greed, ignorance, irresponsible and tragic, indicating a prioritisation of the main issues where environmental issues are at the top. Then power. Then decolonisation. Hudson believes that these five features of modern society combine to give the social and intellectual elite more confidence and the masses much less, which consequently means that the most important objective of museums is to give visitors confidence.

Almost twenty-five years after these views were presented the question is whether this objective is still the most important. Does it in fact need to be adjusted? In 2008 Janes writes about the social responsibility museums have and points out five tectonic stresses that accumulate deep beneath the surface of our societies and that he believes museums have the responsibility to present and discuss:

1. Population stress arising from differences in the population growth rates between rich and poor societies, and from the spiraling growth of mega-cities in poor countries;

2. Energy stress – above all, from the increasing scarcity of conventional oil;

3. Environmental stress from worsening damage to our land, water, forests and fisheries;

4. Climate stress from changes in the makeup of our atmosphere; and,

5. Economic stress resulting from instabilities in the global economic system, and ever-widening income gaps between the rich and the poor (2008:22).

Catching sight of what has changed since 1987 when Hudson ranked environmental issues first is not difficult. The global concerns on Janes’ list cover population, energy, climate and environmental issues. The military industrial power complex and decolonisation issues are left out as are the specialisation of knowledge and the gap between people in positions of power and influence and the masses. Janes presents the five issues in a perfunctory way, even the word ‘stress’ can be construed as neutral. Nevertheless he has expectations about what museums need to do, stating “It appears that we need to move beyond the rational and start talking about values, our emotions and … our principles of right and wrong” (Jenkins 2008:22).

Here we are at the core of the discussion on dynamic events occurring in the plethora of transient activities in and outside the museum. The ethical questions and the relevance of the issues selected and presented relate to what Hudson stresses as the most important aim museums have, i.e. giving visitors confidence. From a communication research perspective these five issues of importance for socially responsible museums come from a sender perspective, i.e. that of society and museums. It is the responsibility of museum curators and organisations to address and push forward these important issues.

Users, visitors and other individuals may define this responsibility differently. Phenomenologist Alfred Schutz (1970) finds that the relations in people’s lifeworld are determined by three types of basic and interdependent relevancies: 1) motivational relevance is governed by a person’s interest, prevailing at a particular time in a specific situation and it only works satisfactorily in situations whose general features and ingredients are sufficiently familiar; 2) topical relevance is where the unknown or problematic in a situation becomes relevant only insofar as it blocks the forming of a definition of the situation and it becomes the theme of their cognitive efforts. People must turn themselves from a potential actor into a potential problem solver and they must define what the problem is; and 3) interpretational relevance is an extension of topical relevance. The recognition of the problem itself and its formulation as a problem necessitate further interpretation. A new interpretation can only be accomplished by putting the problem in the larger context of the frustrated actor’s knowledge, which, the actor surmises, has bearing on the understanding of the problem (Wagner 1979:22-23).

These different views and commitment to what exhibitions are about makes the founding elements for a concrete exhibition fertile soil for dilemmas and conflicts. Museums and curators have the power to define what is important for them to present and persuade an audience with. In the end, it is the various individual visitors and users or non-visitors and non-users who have the power to accept or reject the attempts to be included.

Snow White – out of the realm of the art space

A major Swedish newspaper’s front page story is surprisingly about a contemporary work of art placed outside in the courtyard of a gallery, where a little, yet predominant white boat with a flag with an oval black and white portrait of a young woman with red lips. The little boat floats in a pool of red water or blood and there are two people standing by the pool looking at the white boat or at the photographer and us – the readers. A floodlight stresses the artificiality of the situation.

Ill. 2: Snow White in the courtyard of the Swedish Museum of National Antiquities. An art installation by Dror Feiler and Gunilla Sköld Deiler (2004). Press photo by the Museum of National Antiquities. Ill. 2: Snow White in the courtyard of the Swedish Museum of National Antiquities. An art installation by Dror Feiler and Gunilla Sköld Deiler (2004). Press photo by the Museum of National Antiquities.

What was this front page story all about? The story, it turns out, was not about the installation, Snow White and the Madness of Truth, jointly created by Israeli-born Swedish composer/musician Dror Feiler and his Swedish wife, artist Gunilla Sköld Feiler. The small white boat is called Snow White and the portrait is of Hanadi Jaradat, a Palestinian suicide bomber. Bach’s Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut (My Heart Swims in Blood), Cantata 199, is playing and the following text is written on a nearby wall, “My heart swims in blood / because the brood of my sins / in God’s holy eyes / makes me into a monster”. According to the artists, the installation was designed to “… call attention to how weak people left alone can be capable of horrible things”. A display in the courtyard contains a text that alternates between bold quotes from the Brother Grimm’s original Snow White and the artists’ own musings in italics:

Snow White and the Madness of Truth

Once upon a time in the middle of winter

For the June 12 deaths of her brother, and her cousin

and three drops of blood fell

She was also a woman

as white as snow, as red as blood, and her hair was as black as ebony

Seemingly innocent with universal non-violent character, less suspicious of intentions

and the red looked beautiful upon the white

The murderer will yet pay the price and we will not be the only

ones who are crying

like a weed in her heart until she had no peace day and night

Hanadi Jaradat was a 29-year-old lawyer

I will run away into the wild forest, and never come home again

Before the engagement took place, he was killed in an encounter with the Israeli security forces

and she ran over sharp stones and through thorns

She said: Your blood will not have been shed in vain

and was about to pierce Snow White’s innocent heart

She was hospitalized, prostrate with grief, after witnessing the shootings

The wild beasts will soon have devoured you

After his death, she became the breadwinner and she devoted herself solely to that goal

“Yes,” said Snow White, “with all my heart.”

Weeping bitterly, she added: “If our nation cannot realize its dream and the goals of the victims, and live in freedom and dignity, then let the whole world be erased”

Run away, then, you poor child

She secretly crossed into Israel, charged into a Haifa restaurant, shot a security guard, blew herself up, and murdered 19 innocent civilians

as white as snow, as red as blood, and her hair was as black as ebony

And many people are indeed crying: the Zer Aviv family, the Almog family, and all the relatives and friends of the dead and the wounded

and the red looked beautiful upon the white.

This installation appeared in the Museum of National Antiquities (Historiska muséet) in Stockholm, Sweden from January 17 - February 7, 2004. The idea and context presented on the museum website for the installation was that it was part of the Making Differences exhibition, in conjunction with Stockholm International Forum 2004: Preventing Genocide:

The title attempts to pose the question: Does it make a difference? Do we make a difference? Can art, photography etc. make any difference? - in order to engage people in a dialogue about these matters. Many of the shows also illustrate individual people’s work who we believe do make a difference when it comes to opening people’s eyes toward a larger understanding, and a broader view of the issues. Art, journalism and documentaries have a say in forming opinions amongst people.

Done in a responsible way, art can actually have a value and a meaning beyond being just art itself - it can make people reflect on, and better be prepared, for a discussion and understanding of the events of the world.

The goals described on the website in the art sphere of the museum and the exhibition on preventing genocide were transformed into another event and presented differently in the media. The article on the front page was written not by an art critic but by a journalist from the business desk. The article did not review the artwork in an art history context and the central message on tolerance, freedom of thought and diversity got lost.

The Israeli ambassador in Sweden, Zvi Mazel, is the one who got all the attention because of his destructive actions when he came to the exhibition’s opening and saw Snow White and the Madness of Truth. There were reports in the news, and later on television, of the ambassador walking in the dark up to the floodlight and attacking the installation by disconnecting the electric cords and throwing one of the lights into the pond. The ambassador’s attack on the installation quickly became an art scandal, yielding 128,000 hits on Google at the height of the controversy. Sköld Feiler and Feiler were terrorised and threatened with anonymous phone calls, e-mails and letters. The Israeli government tried to force the Swedish government to take the installation down, claiming it was anti-Semitic in nature. The Swedish government stood firm and defended the freedom of expression.

The introduction to the exhibition prepares the ground for entering into dialogue, employing phrases like, “Can art … engage people in a dialogue … a discussion and understanding of the events of the world”. The built-in mechanisms of the news machine demanded focusing on the conflict, while the political system was good at transforming the goal of promoting dialogue and openness into a narrow, propagandist story on anti-Semitism versus freedom of speech.

The phrase on the Swedish museum’s website, “… engage people in a dialogue …” should be seen in the context of what happens in the exhibition sphere when people individually and in pairs walk around, look, talk and reflect with each other. The people in dialogue with one another often know each other well, their openness and rejection of ideas, to a large extent, frequently mirror each other. Their dialogue is governed by the system of relevancies described by Schutz and the desire for new insight is powered by topical and interpretational relevance.

The case of Snow White and the Madness of Truth shows the difficulty in looking at a work of art purely as an object to be look at, walked around, read or heard. There is a need to bring the artwork into the realm of visual culture. American theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff points to the important idea that visual culture is “… defined … by the interaction between the viewer and the viewed, which may be termed the visual event” (Mirzoeff 1999:13).

A limited number of people saw the original Snow White installation in Stockholm during the tree weeks in 2004 when it was on display. The commotion it caused illustrates how it was concretely transformed into a visual event by the Israeli ambassador’s actions and the media’s willingness to add fuel to the fire. The concept of moving the object of the interpretation from the artwork itself and into a variety of contexts created new viewers and new interpretations. The story of how the visual event unfolded and was received underlines the significance of tracing the various interactions that took place to create the visual event. In addition to the process of revealing and understanding the creation of the visual event, it is also essential to recognise and emphasise the diversity of actual viewers or users in the creation of the visual event. In the end, it is the viewers and the users who become the most crucial element in the creation of a visual event.

What do people process in the museum space?

Many years ago Falk and Dirking came up with a brilliant model in The Museum Experience which divides the museum experience into physical, social and personal contexts. They moved the interest away from the exhibition itself and into the experiences of visitors and their learning processes (Falk & Dierking 1992).

In the early 1990s I was struggling with the complex idea of integrating or extending the reception experience with a more productive experience. I was searching for an understanding of what actually happens in museums and exhibitions in the process of viewing, walking, talking and creating. From my perspective, the Museum Experience model lacked the elements I needed to pursue the ideas I was tussling with. Although excellent, the model’s scope and especially its methodological angel were limited. When museum and exhibition visitors and users are the most important part of creating a visual event, relying solely on verbal interviews with them seemed too confining. I found that interview results could be difficult to transform into a concrete and productive practice for professional curators and designers. The data from the visitor process of experiencing and interpreting was missing something. How could I add more and more differentiated information to the process of experience?

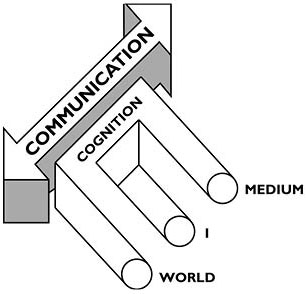

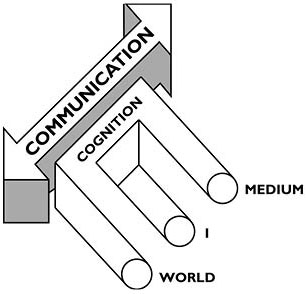

First I reduced the complex setting of the exhibition on site to a more familiar and more manageable medium and situation, namely the production of an article in a magazine by young, non-professional communication students. How did they, as actors and learners, consciously and subconsciously acquire knowledge and experience? There are at least three main areas in which they gain knowledge and experience: medium - I – world (M-I-W) (Ingemann 1992:19). In the following the three elements of the M-I-W model are described.

Ill. 2: M-I-W model: The processes of communication transform the practitioner’s knowledge in three interwoven fields: medium – I – world (Ingemann 1992:19).

Medium: People acquire theoretical and analytical insight into how this specific medium is used as viewers and as producers. Theoretical and analytical aspects are supplemented with knowledge from experience acquired through the concrete productive use of the medium.

Media productions often reproduce the most dominant practice. The core problem in this approach is that transferring intellectual knowledge to practical media production produces the most idiotic, stereotypical solutions. “In order to avoid this we need not refrain from producing, but instead try to develop our very limited knowledge from experience through recurrent and lasting media production … but instead producing more - and more binding productions. To produce with communication as the goal. We want to tell something to someone” (Ingemann 1992:20).

I: Communicating is not an abstract relation between a subject, a medium and a target group. People also learn something about themselves when they set out to communicate a subject. They participate as a member of a group that has reached agreement on the e.g. content, important points, choices, presentation and target group. Thus they need to learn to for example argue their points, make binding decisions, keep deadlines, criticise and investigate. They have to learn to relate to people who are different from they are when they seek information on the subject and the target group. They already have some knowledge, but it is extended and altered in the process involved in creating a media product.

World: In order to communicate something to someone there must be a decision as to what to communicate. The goal of communicating led the communication students to be more specific and more aware of the relevance to themselves and to their target group, but also to being more informed about their core issues of interest. They realised they needed to know more than they ended up communicating and that they needed to address counter arguments. The concept of communicating forced them to clarify their ideas and the topic in order to transform them into their own words, pictures and layout. Strict layout and design requirements for the content forced them to extend their knowledge even further.

Using the M-I-W model and conducting numerous communication production workshops gave the young participants not only broader insight into the media used and their own identity formation but also a deeper understanding of the world. The user-generated content was time consuming to produce and the amount of material resources needed was substantial. The processes of greatest interest were difficult to document because the creative processes mainly involved tacit knowledge (Polany 1967).

The problem I wanted to solve was how to transform the production insights gained from the workshops and the M-I-W model into a form that was applicable to the realm of museums and exhibitions. As a result I established a ground rule that the subjects participating in my area of research interest, documenting visitors and users’ way of walking and talking related to the media, to their identity and to the content of the exhibition, had to know each other and would be selected after speaking to me in person. Visitors would see the exhibitions in pairs. My primary goals were to:

• Capture the ordinary dialogue between the two people walking through the exhibition.

• Capture how they moved and where they moved in the exhibition in order to record what they were looking at while in dialogue with one another.

• Interrupt their visit to make them aware of their own behaviour so they could step outside of their experience to dialogue with for example the researcher.

• Give people tools to express their concrete and emotional dialogue while using the exhibition. Contrary to Falk and Dierking I wanted to capture their experience in the unique moment of experiencing it.

Focusing on the processes of experiences with the person-in-situation provides a unique opportunity to get close to the media, the identity and the content communicated. I wanted to solve the problem of documenting the subtle and tacit knowledge in the creative and productive processes of relating to an exhibition as a visual event. I wanted to capture or better produce their dialogue and their walk and talk by producing a video, but the process had to be easy and involve simple technology. In 1993, when I came up with the idea, video cameras were heavy as well as difficult to use and produce with. Five years later tiny video cameras the size of a fountain pen were available, thus making it possible to design what I call the video-cap. Its size allowed the collection of rich material on the processes involved in creating experiences in an exhibition. The video-cap successfully made it possible to study in depth the person-in-situation, their dialogue and what they experienced while walking around.

Phenomenological experiences

Project partner Lisa Gjedde and I jointly developed the concept of experience and processes to look at the museum and exhibition experience up close (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:99). The aim of examining the experience itself led us to work from a phenomenological point of view and to look for the subjective understanding and meaning of the experience. According to Schutz the everyday world of activity represents what is archetypical for our experience of reality and that what he calls province of meaning can only be seen as modifications of this archetype. Schutz believes that the province of meaning is the art, the fantasy, the play, the insanity and the science, each of which has its own cognitive style (Schutz 1962:231).

We want to understand the mediated situation from the perspective of people’s everyday lives by an emphatic understanding of their subjective universe of meaning. From the phenomenological standpoint, we want to investigate the world as the participants experience it. This concept leads to an interest in what the subjective meanings are and how they are constructed. In the process of developing methods on how to research experience we have found ways to capture different aspects of how the person-in-situation creates meaning and we have applied approaches and concepts relevant to that. In our book Researching Experiences, we provide a framework for researching experience that draws on new models of experience as well as models of reading strategies and narrative thinking combined with detailed descriptions of the use of technologies for capturing experiences. This original contribution to the development of the methodological field of researching experience is called the ReflexivityLab.

The four themes in this book

My initial research question behind writing this book was why objects, showcases and exhibitions are so important. In my attempt to address this serious question and the challenges the areas involved present, I looked at the museum from the outside position of an ordinary user and from my own lifeworld. In brief I discovered or reaffirmed that the concept of contemporary art and especially relational aesthetic opens up for challenging views and acknowledgements; that defining the important issues at stake and their communication is essential for my research; and that knowing what and how people experience exhibitions and create relations, not to mention learn and create identity, is exciting.

These issues, which make up the framework of this book, were also identified as a result of unconscious, even hidden, motivation and cues derived from more than ten years of research. The projects I have developed did not evolve from a systematic coherent plan but arose most frequently from random coincidences and opportunities, but especially from the inclination and desire to pursue research and research tools in my field. Another essential feature has been the shear enjoyment and fun involved in developing ideas and writing.

Some of the following chapters were originally published in Danish, but their content and form have now been transformed in the process of being translated and edited. Collecting material for the twenty-four chapters in this book surprisingly meant discovering many new topics to be explored.

Divided into two main parts, the first half of the book focuses on the meaning making of visitors and how they are given the opportunity to interact and create their own experiences. The second half of the book focuses on the meaning making process of the curator/designer used to establish the decisive relation of form and content in an exhibition. The original concept was to investigate the creative processes of assemblage and creation closely aligned with the development of the concept and the aesthetics.

The title of the book, Present on Site: Transforming Exhibitions and Museums, is intended to encompass the active, creative involvement and interaction of visitors and curators/designers in the exhibition/museum. The aim is to learn something from the process of being a visitor and the practices involved (Soren 2009:234). The focus is not the works of art. Nor the objects. Nor the installations. The processes involved in being present on site are something one does and something one does better by doing them. The processes represent the values presented and the struggle to define, contest and support those values.

The first half: Constructions and questions

The first half is divided into two themes. The first theme, Construction - The visitor at an exhibition, is significant from the curator’s point of view, where the exhibition is clearly built up of individual and specific objects, while from the visitor’s point of view the exhibition is primarily seen as a whole and as a narrative. Two major theoretical frameworks in the book are narrativity and the concept of the Model User as the competences the implied reader, viewer or visitor must have to understand and get something out of an exhibition. The visitor needs to have specific knowledge, attitudes and understanding to be included and accepted as a ‘good enough’ visitor and to be qualified to gain insight, acceptance and recognition. To make anything worth devotion there must be access to it and this access or entry way is the user’s questions regarding the issues at stake and how they are framed.

In the second theme, Questions - Experience and learning processes, attention, reading strategies and relations are studied as processes of meaning making as they appear in the actual visitors’ experiences. These experiences are seen with the phenomenological reflexivity of action, situation and reality in the various modes of being in the world through the person-in-situation. The question is addressed as to how the person-in-situation constructs his or her identity and learning in the process of interaction with the actual exhibition. Another question is how the visitor constructs the experience with a clear start, conclusion and cohesive trajectory with a sense of fulfilment, unity and completion (Dewey 1934/1958).

The second half: Invisibles and Openings

Like the first half, the second half is divided into two themes. In the first theme, Invisibles - The exhibition design process, the epistemological interest is to unveil the subtle processes that take place when information, objects or moods have to be formulated, presented and communicated to an audience. This is the moment in the creation of concepts and ideas in a specific context and sometimes at a specific site. Through introspection, an intense reflection-in-action reveals the development of concepts for an exhibition in the creative process. The role of the media artist and designer is contested to clarify and talk about the difficult and often invisible design processes. The projects studied in this book reveal prototypical challenges and problems in relation to the communication milieu, institutions, content interpretation, communication and poetry.

The second theme, Openings - Category, objects and communication, deals with the intended content presented and used by a recipient. Communication however is not only form; it is also always the decisive content/form relation. A close look at museums in the first steps of the decision phase about an exhibition shows that central concepts such as original objects, authenticity, dialogue, taxonomy and user involvement emerge. This theme examines these concepts without providing answers as to how to do exhibitions that are more open and inclusive. The issues discussed form a basis for a more communication and design-oriented practice around the use of exhibitions on site as well as for looking even closer at the process behind producing exhibitions and involving the users, the users as visitors and the users as professionals (or amateur curators/designers).

The Danish framework

Why is it necessary to cross the Channel to have a different perspective and what is so different? A common opinion is that Anglo-American museology tends to be more pragmatic, more quantitative and more result-oriented. Danish museology, at least from my perspective, is more phenomenological, more creative and more qualitative, while the framework is theoretically visual culture focused on the visual event, i.e. the complex and rich interaction between the viewer and the viewed in the meaning-making process.

For obvious reasons, the cases presented predominantly stem from stationary and temporary Danish exhibitions, thus giving them a unique, exotic element, just as anything that comes from a different culture bears its own special traits. Even in a globalised world, dialects exist determined by local circumstances. It is not without coincidence that the anthology I co-edited is called New Danish Museology and stresses the distinctive local Danish angle (Ingemann & Larsen 2005).

|